The question of the efficacy of the grid system is continually interesting, and there have been some interesting conversations about this with a range of folks locally. Another resource to throw some information into this discussion is the recently released background documents in support of the Portland Plan. One worth checking out for any Portland-phile is the segment on Urban Form (it’s a large file, so this is a link to all of the background reports).

Scrolling through it, I found this interesting two page study on block typologies, which mentions the ubiquitous 200′ square blocks:

:: image via Portland Plan

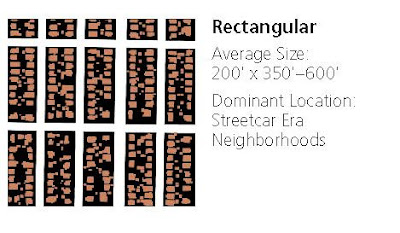

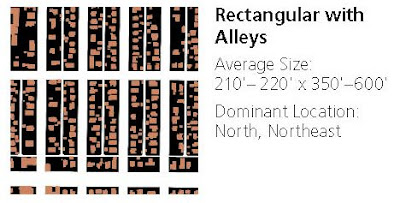

From page 37-38 of the Urban Form document: “A city’s structure of streets and blocks serves as its urban DNA, shaping its development long into the future. While Downtown Portland’s system of compact 200′ by 200′ blocks is sometimes seen as Portland’s fundamental pattern, it covers only a small part of the city. As will be summarized in this chapter, Portland includes a diverse and varied range of urban patterns. These examples highlight the wide range of block structures found in Portland (they are not intended to represent what is typical or most common).”

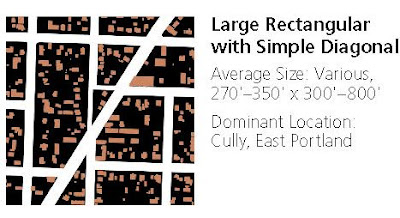

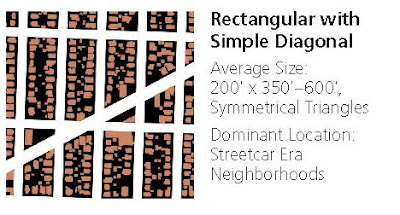

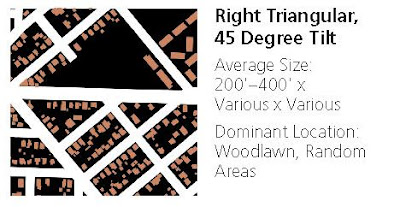

This couple of pages continues to outline a range of variations, also giving an average size and location that they commonly appear within the city. The grid obviously starts to stretch in some areas, turning into a rectangular grid with one elongated side and the inclusion of alleys in some areas. These are bisected by some of the anomalous items like diagonal streets. There is also a larger retangular block size as growth sprawls out into Northeast and East Portland.

:: image via Portland Plan

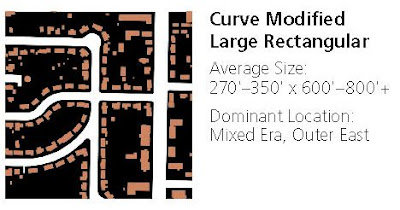

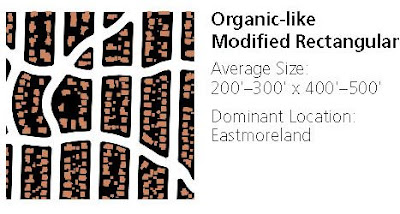

The square and rectangular blocks degrade in a number of ways, including some neighborhoods that have a more diagonal grid that creates triangular blocks and open spaces. Subsequent iterations include more curvilinear blocks are rectangular grid but with undulating curves, and some more organic layouts that may or may not have been influenced by topography.

:: image via Portland Plan

As you can see, there is definitely an evolution away from the small grid, which is mostly located in the City Center and inner eastside. It’s also interesting to see the changes and experimentation that happened as the city moves outward from the center. But wait, there’s more… another set of typologies to augment these patterns that offers some more typologies, including the very archetypal Ladd’s Addition, an beautiful oddity for sure, as well as plain ol’ curvy sprawl. It’s a fascinating study.

:: click to enlarge – via Portland Plan

These patterns aren’t necessarily the all-encompassing group, but it does outline a vocabulary of almost 20 varieties that range from the prototypical 200×200 block. I spent a couple of days in San Francisco this past week, working on a project, and it was interesting to contrast a small grid with a comparably large one, particularly at a pedestrian scale. It was a block-by-block decision whether this made one or the other more successful – but it wasn’t a particular winner either way. Along that line, check out my colleague Brett Milligan and a couple of posts on his Free Association Design blog about the grid and a case study of vertical subterranean structure from Guanajuato.

More to come on the comparisons, for sure and definitely more on the Portland Plan and associated documentation. For those interested, check out the latest community involvement dates to see where the Plan is going…

Jason,

Great post! It is really interesting to see this diagramming of Portland’s street structure. It helps to understand more of the diversity of the city and start to get a sense as to what the designers were thinking about in the different areas.

In response to your comments on the previous post, I totally agree that the original article on Planetizen was a bit unfair to Portland. The grid is not a Portland invention and the size of Portland’s grid should only be part of a much larger discussion.

There are lots of examples of cities that use non-grid street layouts to organize the city. Most of them are very old. They were developed in such a way that blocks with houses on them were thinner then blocks with other types of buildings on them. Markets and government buildings were central buildings and streets radiated out from them because these places were frequently visited and transportation was hard because it was all very lo-tec. This type of system is both more complex and more simple. It allows for both greater possibilities in block geometries since you are not worried about maintaining an arbitrary grid and you get an obvious prioritization of corridors.

What I think cities need to do more of is to really evaluate how people are moving around in and entering their cities. Then figuring out what the pros and cons of those methods are and adjusting how they allow people to move about based off of that information. Plans of expansions of cities need to be planned the same way.

Jason,

Great post! It is really interesting to see this diagramming of Portland’s street structure. It helps to understand more of the diversity of the city and start to get a sense as to what the designers were thinking about in the different areas.

In response to your comments on the previous post, I totally agree that the original article on Planetizen was a bit unfair to Portland. The grid is not a Portland invention and the size of Portland’s grid should only be part of a much larger discussion.

There are lots of examples of cities that use non-grid street layouts to organize the city. Most of them are very old. They were developed in such a way that blocks with houses on them were thinner then blocks with other types of buildings on them. Markets and government buildings were central buildings and streets radiated out from them because these places were frequently visited and transportation was hard because it was all very lo-tec. This type of system is both more complex and more simple. It allows for both greater possibilities in block geometries since you are not worried about maintaining an arbitrary grid and you get an obvious prioritization of corridors.

What I think cities need to do more of is to really evaluate how people are moving around in and entering their cities. Then figuring out what the pros and cons of those methods are and adjusting how they allow people to move about based off of that information.

Thanks Scott.

It’s an interesting idea of looking at urban form, particularly when they were ‘laid out’ in a more organic way versus a more ‘planned’ approach – and which is better. The fact that we don’t allow anything to organically evolve for the most part makes me think that we could lose that organic form-making – and we will continue to apply what we think is our best bet (which constantly changes). Either way, the cities will be variable – as is shown in the historical change of Portland urban form – and it’s up to what we do with them to determine success.

I’d love to see the ideas of landscape urbanism and the priciples of temporality and flexibility of form applied to an urban area – allowing for some framework for infrastructure but also some ability to change and adapt into the future in more appropriate ways, not saddling ourselves with what we thought worked 20-40 years ago.