A great feature from Spiegel Online covers the work of Azzam Alwash, a US/Iraqi hydraulic engineer aiming to restore what were once vibrant wetlands flourishing in the cradle of civilization through an organization called Nature Iraq. While most news coming from the region focuses on bricks and mortar rebuilding, it’s important to note the power of restoration of ecosystems in rebuilding efforts. The connection between people and land is vital.

:: image via Eden Again

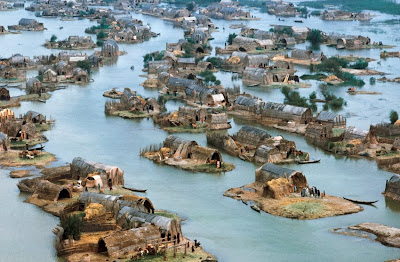

The area was originally marshland fed from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. From the article: “Only 20 years ago, an amazing aquatic world thrived in the area, which is in the middle of the desert. Larger than the Everglades, it extended across the southern end of Iraq, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers divide into hundreds of channels before they come together again near Basra and flow into the Persian Gulf.”

This is especially evident in satellite photos of the region from 1976 and 2002, showing the widespread ecosystematic destruction of the marsh.

:: images via Spiegel Online

From the article, the motivation is clear:

“The official explanation was that the land was being reclaimed for agriculture. The military was sent in to excavate canals and build dikes to conduct the water directly into the Gulf. The despot, proud of his work of destruction, gave the canals names like Saddam River and Loyalty to the Leader Canal.

In truth, Saddam was not interested in the farmers. His real goal was to harm the Madan, also known as the Marsh Arabs. For thousands of years, the marshes had been the homeland of this ethnic group and their cows and water buffalo. They lived in floating huts made of woven reeds and spent much of their time in wooden boats, which they guided with sticks along channels the buffalo had trampled through the reeds. They harvested reeds, hunted birds and caught fish.

When the fishermen backed a Shiite uprising against the dictator, the vindictive Saddam turned their “Garden of Eden” into a hell. He had thousands of the Marsh Arabs murdered and their livestock killed. Any remaining water sources were poisoned and reed huts burned to the ground. Many people fled across the border into Iran to live in refugee camps, while others went to the north and tried to survive as day laborers. By the end of the operation, up to half a million people had been displaced.

Within a few years, the marshland had shrunk to less than 10 percent of its original size. In a place that was once teeming with wildlife — wild boar, hyenas, foxes, otters, water snakes and even lions — the former reed beds had been turned into barren salt flats, poisoned and full of land mines. In a 2001 report, the United Nations characterized the destruction of the marshes as one of the world’s greatest environmental disasters.”

The use of ecosystems as essentially a weapon against people is striking – a much more appropriate usage of the term eco-terrorism (versus it’s common parlance) or at the very least eco-despotism… (although a quick google search of that term yields a totally different meaning). A future post at least on the linguistics of that one I imagine 🙂

The view from 1976 shows what was once a thriving ‘human ecosystem’ supporting wildlife as well as economies of small reed farmers, fisherman and shrimpers… followed by a representative shot of the area prior to any restoration activities.

:: images via Spiegel Online

The restoration is ongoing, and an amazing story of folks (Alwash and others) risking their lives to restore the ecological and cultural heritage of a vital global region – folding in conservation and humanitarian needs to offer an alternative scenario to ‘rebuilding’ after devastation occurs. While public works, dams, roads, electrical grids, and schools offer much by way of infrastructure to support a society in transition, the ecological is an important aspect not to be overlooked. There are lessons here that perhaps we can implement in our own disasters (both ‘natural’ and man-made) and remember the connections between resiliency in the human as well as the ecological systems.

Check out the rest of the article here.

There was a conference in 2004 at Harvard titled “Mesopotamian Marshes and Modern Development” that included Azzam Alwash. Out of this came a book with a difficult title “Restorative Redevelopment of Devastated Ecocultural Landscapes” edited by France. Possibly a bit dated, but a good overview of the issues and potential strategies to improve conditions in southern Iraq. The big problem though still is upstream impoundments.

Excellent article, thank you!! What strikes me as the worst part of this ecological transformation is its permanency. Desertification is a very tough trend to reverse, just look at Africa’s Green Belt. Eden’s desert – along with the acts of cruelty, torture, and inhumanity under Saddam – may be the lingering legacy of the era.

Iraq land is the land full of historic moment of humanity. Make peace this land, will peace the worl.