As mentioned in the previous deep dive into the recent IPCC Special Report, this city-specific version of includes a Summary for Urban Policy Makers, from December, 2018, giving a bit more context on the impacts summarized in October the 1.5°C of global warming, specifically focused on what it means for cities. As mentioned, “Climate science must be accessible to urban policymakers, because without them, there will be not limiting global warming to 1.5 °C” (p.6)

Going further, the summary touches on elements that have been covered previously, so the focus here is on the ‘urban specific’ info. The connection to policymakers here is both to focus attention, but also to “serve as inspiration and resources for solutions in other urban areas”. This is interesting to me, as it takes broad information and focuses it on a context in which landscape architecture and urban design, along with planning and architecture operate. The original IPCC report “identifies cities and urban areas as one of four critical global systems that can accelerate and upscale climate action,” recognizing that “this will require major transitions in how both mitigation and adaptation are undertaken.” (p.6)

The scale and scope of climate change is reiterated here, and it is acknowledged that there are some initiatives happening in urban areas, but that more needs to happen. Of the four key systems where changes need to occur, one is specific to cities: Urban and Infrastructure, but all of the others, Energy, Land Use and Ecosystems, and Industry, all have critical urban interfaces.

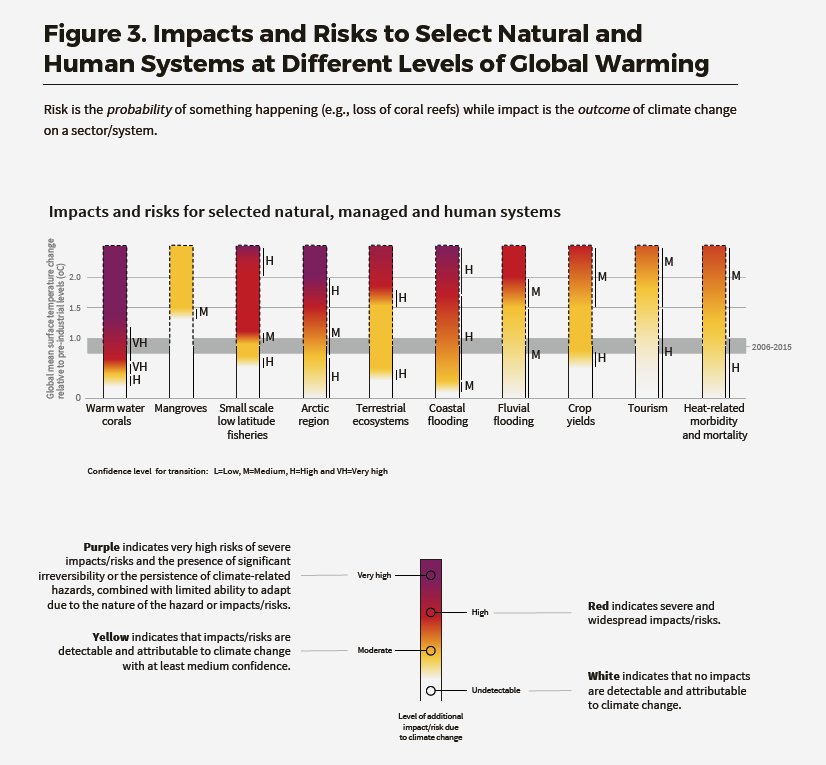

The impacts as well may be exacerbated in urban areas. For instance mortality due to heat islands or urban coastal and inland waterway flooding is magnified due to large populations of people in urban zones. Similarly water stresses in urban areas can leave many without drinking water supplies, which will become more significant with more intense drought conditions and heat waves. The figures in this report are similar to the original Summary, but are reformatted – such as Figure 3, which outlines some of these climate impacts and their risks.

The report does echo other voices when discussing the magnitude of the issues, as well as the fact there is little historic precedent for the impacts and changes. Thus new ‘rules’ apply everywhere, and must be applied specific to cities. While the impacts of cities are large, there are also many opportunities such as mitigation, and very necessary pathways to adaption, which must “describe how people, communities, and systems adapt in a dynamic, iterative, and flexible manner to the impacts of climate change.” (p.13). In particular, understanding how things differ across sectors and geographies, as well as addressing vulnerabilities by tapping into local knowledge and involving a range of stakeholders.

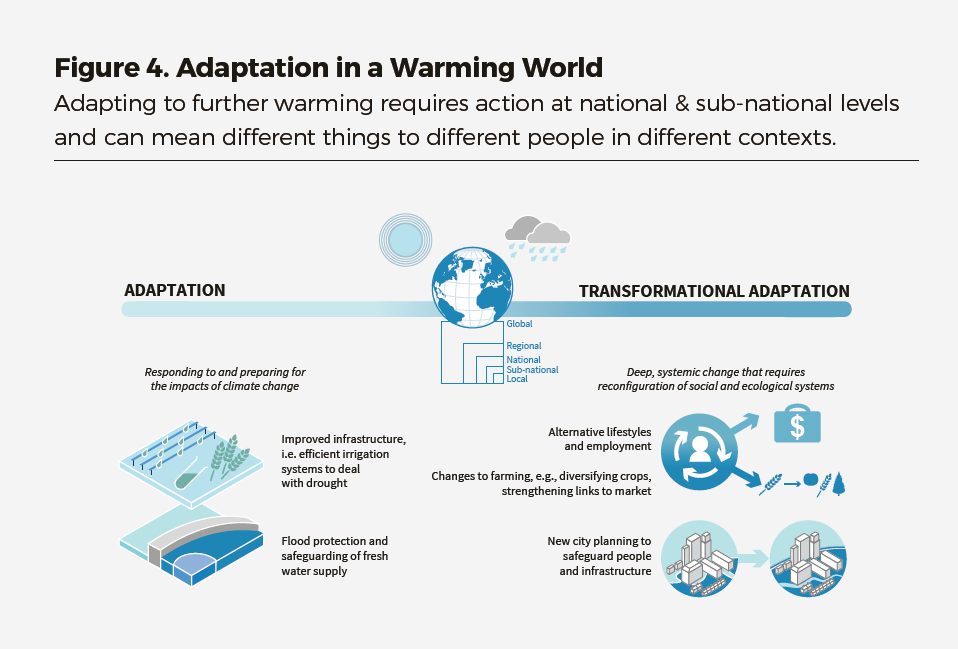

As shown in Figure 4, this multi-scalar adaption gives a lot of agency both to planners and designers, working on the ground in applicatoin or development of policies and codes. It also means understanding that the concept “can mean different things to different people in different contexts.” The difference in this case between reactive adaptation, which implements strategies like infrastructure improvements for drought, or flood protection, and a more holistic ‘Transformational Adaptation”, which includes “Deep, systemic change that requires reconfiguration of social and ecological systems.” (p.13)

In the end, incremental strategies are not going to be sufficient, so planning is critical to provide national, sub-national, and regional strategies at appropriate scales to make a difference. Per the report:

” Transformation adaptation seeks deep and long-term systemic changes that can accelerate the implementation and localisation of sustainable development to enable the transition to a 1.5°C world. It implies significant changes in the structure or function of an entire system that go beyond adjusting existing practices.” (p.13)

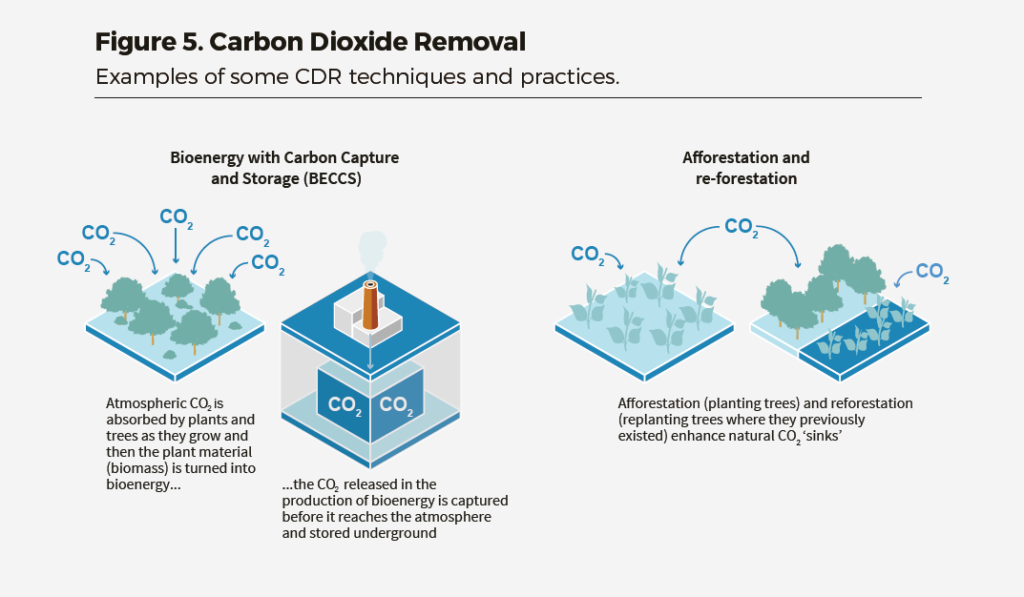

Thus changes can occur at a governmental level, but this can influence individual actions that work at a local level. The systematic changes mean cities working in partnership with larger regional and national governments, to focus sustainable development on the economy of cities, urban form, infrastructure, and connections between urban and rural areas. This is important in the context of carbon dioxide removal strategies (CDR) which can provide synergies between use plant biomass for energy (which can be sustainably managed outside of cities) and proximity to areas where energy use is most in demand (areas inside the cities). Afforestation is another opportunity that seems to be more rural-focused, but I feel there’s an interesting opportunity to employ urban afforestation that also provides many co-benefits like health, air pollution reduction, reduced heat gain, and more.

Part II gets specific in applications of the report to cities, and provides the context for ‘why it matters’. The stats are well known, but significant: more than half of the worlds population lives in cities, and most of the built assets and economic activity also live there. Urban populations are also growing, and will be two-thirds of the world population, as over 70 million people move to cities each year. This has implications for climate mitigation as new buildings, which alone account for 1/3 of global energy consumption, will need to be built, offering an opportunities for more efficient, less carbon intensive structures, making the expansion “a catalyst for new technologies, buildings and infrastructure” that has very low or now emissions. (p.16) This needs to be scaled up to have impact:

“The global building stock in place in 2050 will need to have 80 to 90% lower emissions than 2010 levels to achieve a 1.5°C consistent pathway. Such a pathway also requires a minimum 5% annual rate of energy retrofits of existing buildings in developed countries, as well as all new buildings being built fossil-free and near-zero energy by 2020.” (p. 16)

This happens in construction, in particular reducing the impact of high emissions materials like concrete and steel, along with adoption of scalable smart girds using renewable energy strategies such as solar, wind, and geothermal. Additional building systems strategies could include better industrial development that is less polluting, and the opportunities to use waste heat, water, or other materials to support other buildings. There are many other benefits beyond buildings, including transportation system changes, which can reduce car use by implementation of compact, transit friendly, multi-modal walkable and bikeable neighborhoods, making lifestyle changes possible.

Specific to landscape architecture is the key role that landscape systems can play in supporting ecosystem services in urban areas. For instance, “green infrastructure with increased use of nature-based solutions could reduce flood and drought, enable water conservation and reduce urban heat island effects.” (p.16) Furthermore, these zones of plants and soils can help with carbon capture to amplify mitigation and creating cities that are “sinks for carbon” by planting urban forests, growing food, and use of sustainable wood products. There are also contextual opportunities, including coasts, wetlands, and rivers that can all be “employed to sequester carbon.” The co-benefits are mentioned above, and the key benefit for all of these interventions is that:

“…their effects can be amplified by the density of cities and urban areas.” (p.17)

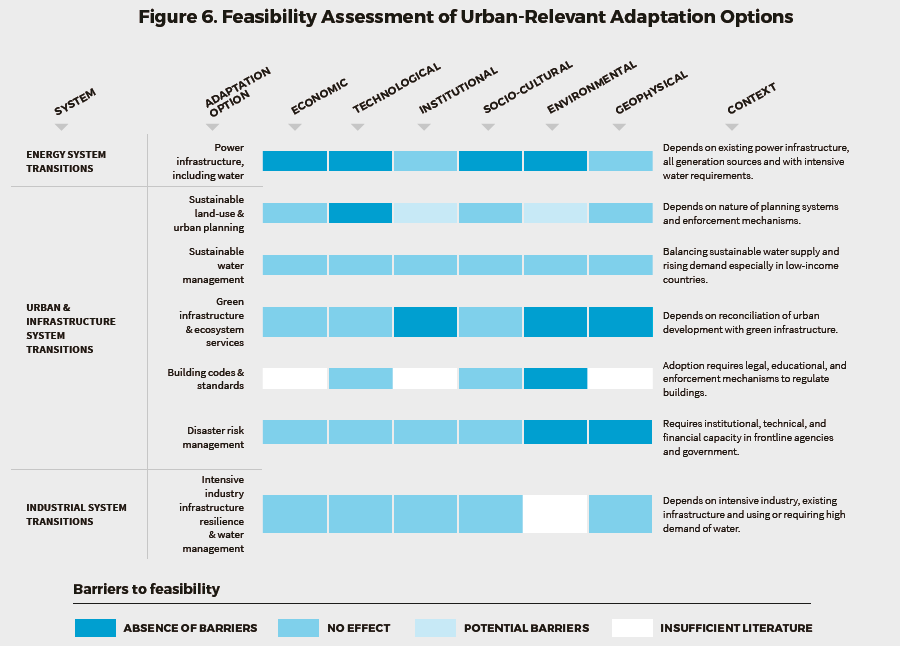

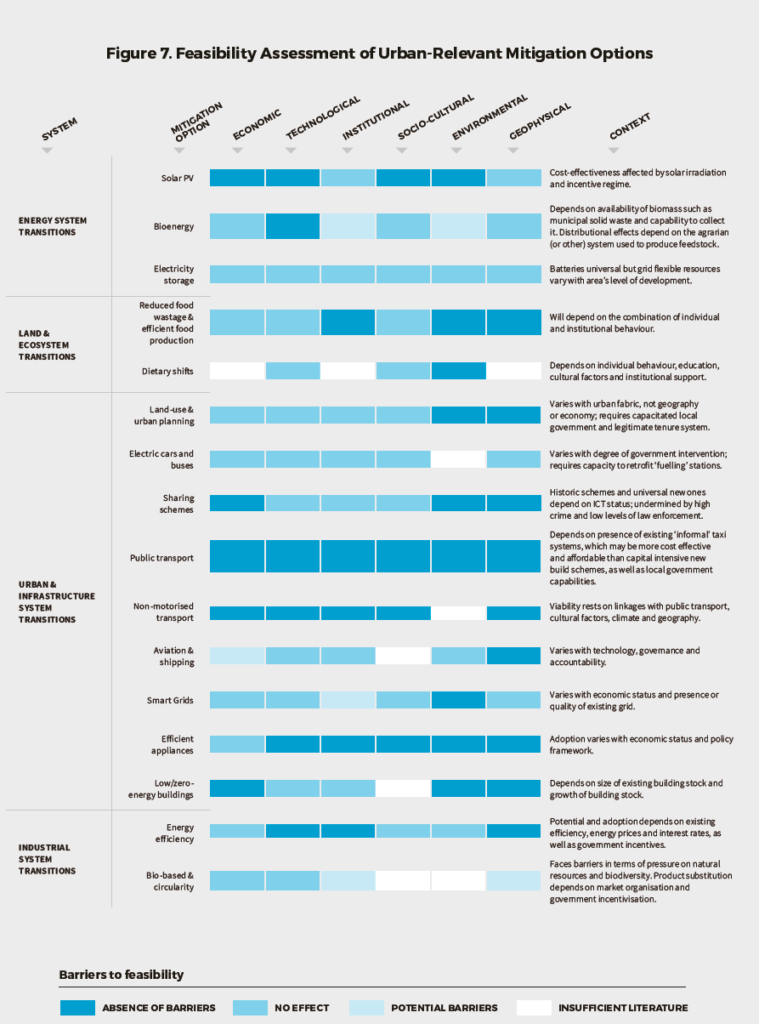

Section III looks specifically at feasbility, and is worth exploring for lists of potential solutions. While the success of solutions is dependent on many thing, including “geophysical, environmental, ecological, technological, economic, social, cultural, and institutional factors”, there’s also the potential of cities, to aggregate these factors. (p.18)

This idea of Multi-dimensional feasbility is important, which looks at the above factors, but also the interplay between positives (synergies) and negatives (trade-offs) that occur with any decision. Examples in the report point to options that have the ability to maximize both adaptation and mitigation, for instance wetland restoration which captures carbon while also providing resilience from flooding. Trade-offs, on the other hand could be providing more density to aid in compact communities, which has a negative of increasing urban heat island effects and reducing natural areas and biodiversity.

I think it’s worth listing for reference the mitigation and adaptation strategies in the report (p.19) as they give a good blueprint for opportunities in the urban environment, many of which are actions accessible to use today.

- Urban mitigation options

- solar photovoltaics and wind w/ battery storage

- bio-energy

- energy efficiency

- efficient appliances

- electric vehicles

- better public transport & local shared mobility

- non-motorized transport

- low-energy buildings

- reduced food waste

- ecosystem restoration

- more sustainable land-use and urban planning

- Urban adaptation options

- conservation agriculture

- efficient irrigation

- green infrastructure

- ecosystem services

- community-based adaptation

- appropriate building codes and standards

Connecting to the larger UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) gives context for these synergies and trade-offs as well, which points to another main difference in this urban specific report is a detailed feasibility assessment of the above measures. According to the report, this is the first time such an assessment has been tried, with a goal to assist in identification of options, help prioritizing actions, and assessing feasibility related to synergies and trade-offs by looking at the options using the six dimensions: “economic, technological, institutional, socio-cultural, environmental/ecological, and geophysical.” (20-21)

Figure 6 focuses on adaptation and Figure 7 is specific to mitigation options – click to zoom (or download the PDF of the report for a clearer picture)

The final sections focus on implementation, and integrating this at a policy and community engagement level, employing multiple stakeholders to “enable local adaptive and mitigation capacity.” It was found that success happens most often when this has alignment with both sustainable development and people’s values, and when local and regional initiatives are supported by national policies.

For the most part, local communities lack the capacity to conduct this engagement. This has been minimized somewhat by knowledge sharing of information through means like climate networks where people can share experiences. Technology is also helping to leverage more impact and innovative funding partnerships allows for supporting private companies working on new developments that public benefit. The key element for policy and engagement is that people feel the processes are fair and inclusive, like any good process, it needs to “take into account values, worldviews, and ideologies.” and be clear and transparent about “consequences, financial, social, and emotional.” (23)

Funding is also key – and while cities can contribute they cannot alone solve the issues, so the ability to use multiple approaches and reach out beyond the cities is key. The overall resources as well are not lacking, as mentioned:

“In principle, there is not lack of capital in the global financial system to support the required climate actions” (p.24)

Yet we are still not getting there, and the cost will need to be around $100 billion dollars per year, or around 2.5% of world GDP to tackle this issue. This, of course, means changing systems well more wicked than climate, such as economics, banking, and capitalism itself, but as risk changes, there are shifts happening, such as required “climate stress testing” for companies, and investment portfolios looking to move away from fossil-fuel companies for investors and shifting to renewable and low-emission assets.

To conclude – the report stresses the urgency, and the need to act in the next decade, while reinforcing the role cities need to play in climate change solutions and necessary transitions from our current paradigms to a carbon-free future. In this way:

“Cities offer many of the most readily-available, feasible, and cost-effective options for these transitions.” (p.26)

Cities won’t solve the problem on their own, but have much to offer to “amplify or reduce impacts,” particularly in urban and infrastructure sectors, as well as energy, industry, land use and ecosystems.

This is both an imperative to act for the greater good, but also self-preservation, as many cities will be the ones massively impacted by the cumulative negative consequences of our changing climate.

HEADER: Image of the Cheonggyecheon Stream Restoration in Seoul, South Korea – p.18