In an attempt to be intentional and informed in tying landscape architecture to climate change and asking some of the fundamental questions I posed in my introductory post, I starting to develop a plan and amass a wide range of resources. Even now, I’ve barely scratched the surface, although this initial study has been illuminating, perhaps just in posing more questions.

First, I wanted to focus on climate change mechanisms and impacts, of which there is not shortage of resources, covered in a combination of technical reports, books and articles. Second, I wanted to tap into many of the strategies from design and planning world, of which there is a steadily growing collection of articles and books, to address this in the context of solutions based in landscape architecture, architecture, and urban planning. Lastly, is the rich resource of academic journals and papers that connect the issues and approaches with a layer of evidence to further inform potential solutions. In this initial post I will focus on the first, and relate some of the initial experiences.

Climate Change Reports

One impetus for my recent obsession was the release (to much fanfare) over the Thanksgiving weekend of Volume II of the Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA4). This report gives a detailed account of the “Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States.” Authored by an army of experts, and published by the U.S. Global Change Research Program this is the de facto standard for US Climate Science and has helped transform and amplify discussions.

This is a companion to Volume I, the Climate Science Special Report, which was released in 2017, and dives deep into the science. I’ve not yet read any of the previous report, but Chapter 2 of Volume II provides a good overview summary of Vol I which puts the science in context. The entire Volume II is a mere 1,524 pages, so it’s not a quick read. It’d be great to be comprehensive and absorb in its entirety, but I wanted to do some selective reading that gets the key ideas, and focuses on ecology, water, and built environment.

For instance, I read the following chapters:

- About this Report, Guide to the Report

- Summary Findings

- Chapter 1: Overview

- Chapter 2: Our Changing Climate

- Chapter 3: Water

- Chapter 7: Ecosystems, Ecosystem Services, & Biodiversity

- Chapter 11: Built Environment, Urban Systems & Cities

- Chapter 24: Northwest (Region)

- Chapter 28: Reducing Risks through Adaptation Actions

- Chapter 29: Reducing Risks through Emissions Mitigation

Even with this, it’s still hundreds and hundreds of pages, but was very informative, both in a foundation of understanding of climate science and impacts, specific contexts and impacts to natural and built systems, a snapshot of my particular region, and how communities are addressing adaptation and mitigation in action. For other sections, I read the executive summaries and looked at the Key Messages to fill in gaps. My suggestion, if you have half an hour, find one of the 10 chapters that cover different US regions and dive into that – at least you can connect with key concerns and impacts in your home place.

While the NCA4 focused specifically on the United States, the report from the International Panel of Climate Change (IPCC), which was released a month earlier in October 2018, is more global in scope. The Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C presented the latest science on green house gas emission pathways, with a focus on “strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty.”

Lots to absorb there, and so far, I’ve just read the Summary for Policymakers, which is a shorter, executive summary that breaks down the report into specific key elements. It provided a good context for the full report and both the latest science as well as focusing on the main differences that will happen in a 1.5°C vs, a 2°C rise in global temperature. The summary showed which sections would be helpful to dig into for more info as needed, so will read more in depth in certain areas. If you want a version that is tailor-made built-environment folks like landscape architects and planners, I’d recommend this city-specific version called the “Summary of Urban Policymakers” which provided a focused and more readable account of the special report from the urban perspective.

While it may seem daunting to dive into massive climate change reports, it’s critical to go to foundation documents, a step we often neglect in our haste to ‘find solutions’. It’s also necessary to connect the way we work with the way evidence is generated and communicated. In this regard, a comment by Elizabeth Hamin-Infield in the introduction to the book “Planning for Climate Change“, (which I will cover soon) is instructive, as she suggests that designers and planners need to take the time to engage with these reports:

“Because the IPCC’s work is so central to global scientific understand, it is helpful to get acquainted with the particular communications style of the IPCC… [it] forms a common language across fields and thus encourages interdisciplinary understanding.”

Hamin-Infield, Abunnaser, & Ryan (eds), 2019 p.10

The idea is relevant to the NCA4 as well as other technical reports, highlighting the science and strategies and connecting what you will encounter in mainstream discussions back to the evidence. A key distinction, for instance, made in both reports is to differentiate the concepts of mitigation and adaptation, terms which can have multiple meanings in different contexts, but very specific meanings here. It’s helpful to understand that in common climate change parlance ‘mitigation’ is focused on the measures to reduce GHG emissions, and ‘adaptation’ is focused on our adjustments to the impacts that will result from these changing environments. By using the distinction, we can avoid confusion and clarify intention as we discuss among different disciplines.

This was one of the more important cases, but there were others in my experience that came from reading these reports. First was to develop an understanding of specialized terms that you may hear, like radiative forcing, Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs), uncertainty, or emissions scenarios. In addition, there is clarity to more common terms like adaptive capacity, co-benefits, preparedness, trade-offs, resilience, and risk specific to how they are used in the climate change literature. I even went so far as to start creating my own personal glossary of terms, which was helpful to both understand and later write about these topics. It reinforced the idea in the quote above from Hamin, that a common language is important for shared understanding, especially when we are tackling these from multiple disciplinary perspectives.

Introductory Books

My goal in this post wasn’t as much to dive into these documents as much as to introduce the foundations of the subject matter and how much it can inform designers and planners. Beyond the technical reports, there are many books that present similar information. I’ll highlight two here: one authored by a scientist as a primer on climate change, and the other authored by a journalist reporting on related stories.

I’d highly recommend every read Mark Maslin’s “Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction” which is (as expected) a concise take on climate change covering the science, evidence, modelling and impacts. Chapters also delve into some great topics like climate change denial, political dimensions, and some solutions put forth. After reading the reports above, I got a lot out of this (even though it goes technical at times) in terms of filling in some gaps about specifics, presented in a straightforward manner.

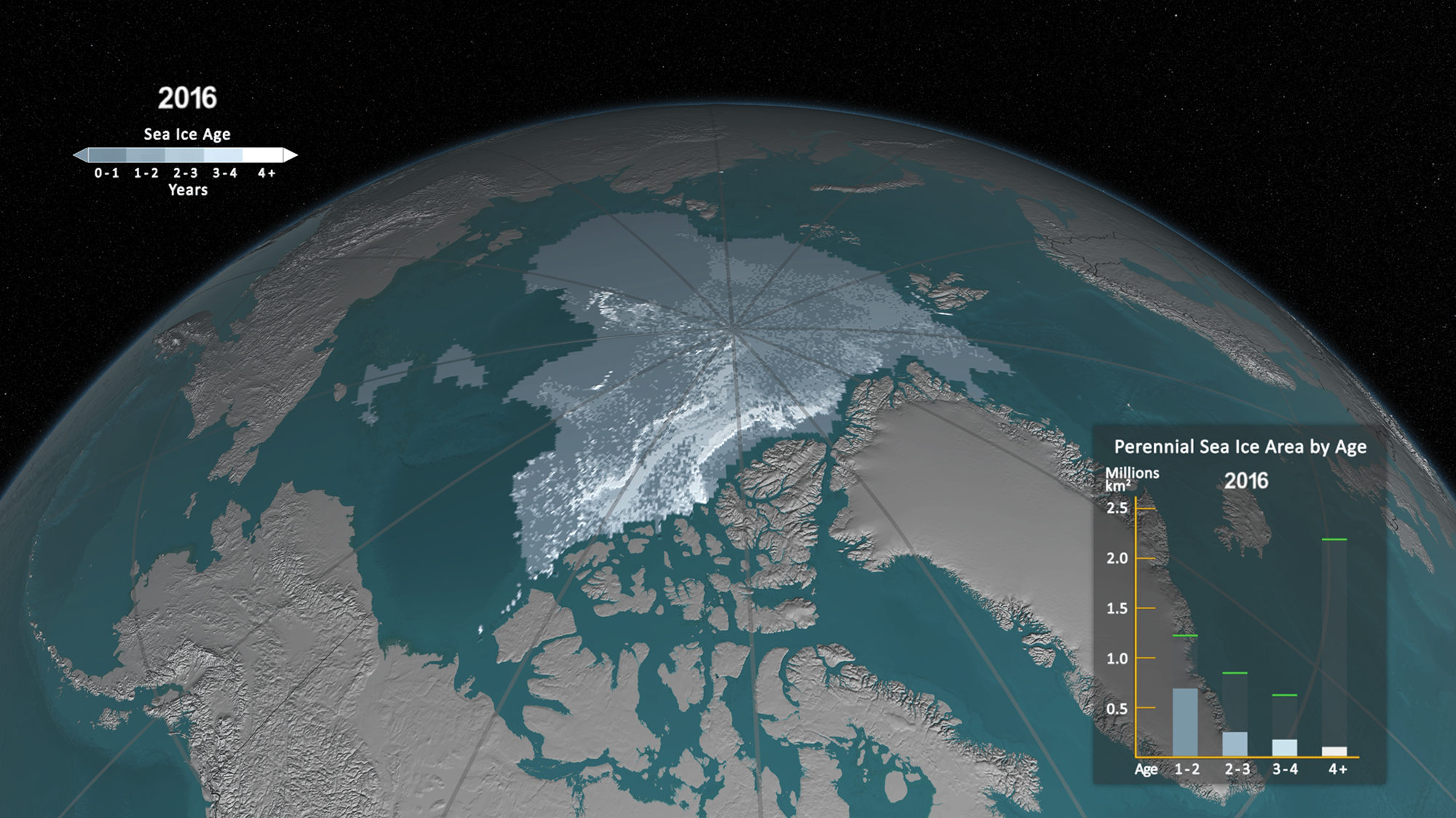

Another well-known book on the subject is “Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature and Climate” by Elizabeth Kolbert. Written originally in 2007 and updated with some new essays in 2015, it’s is an imminently readable overview, that contains equal amounts hard info and engaging stories around the theme of climate change. A compilation of writings collected in the New Yorker, these are a refreshing counterpoint to the density of reports, and often paint a human side to the subject. The goal here isn’t comprehensiveness, but it does paint an illuminating portrait of topics like Alaskan permafrost, the shifting ranges of species, historical climate events, and some interesting solutions.

There are a number of others in this vein worth exploring and I’m sure will get some coverage here on the blog (along with elaborating on these two above). It seems new books are emerging daily as this topic takes hold of our collective zeitgeist. The timeliness is important. For instance, both of the above books were published in the mid-2000s, and while both have been updated more recently, they suffer from one of the big issues with climate change — that it’s changing fast, and that books often are quickly dated. That doesn’t mean they don’t have anything to offer in a broader sense, but it’s important to be aware of old data from a previous IPCC or NCA report used may not align with current understanding . That said, the takeaways are often still legitimate and the continual, upward rise of temperatures and GHG emissions, unfortunately has not changed much.

So much more…

This is the tip of the (admittedly rapidly melting) iceberg. The climate change specific reports put other writings in context and of course expanded to include many additional resources. It also provided a new lens for how we talk about climate change in design realms. For instance, we’ve all read the articles and essays coming from the design community, with tales of combating sea level rise, and innovative resilience methods. I was struck by an often inherent lack of understanding and being able to tie solutions to the fundamental concepts and language of climate change science in much of this mainstream writings. This is not uncommon, and long histories of shallow solutions and green-washing is not new, but in this case, it seems to evoke a lack of validity to claims and erodes our relevance to being helpful actors in this realm.

This is not exclusively true, but common enough to need addressing, and will be explored more in depth, as I’m in the process of evaluating over 300 articles (so far) and it’s fascinating to see the diversity and disparity in our approaches. There is, conversely, a palpable lack of applied solutions that emerge from the scientific reports (which doesn’t surprise me) even though they do contain some case studies and hint at mitigation and adaptation work. The translation each was is still a bit fuzzy, so strengthening this seems appropriate.

Perhaps that’s a good starting point, and one that exists throughout our search for good evidence-based design strategies. And one I mention often. Designers needing to be more informed on the way science works and how to engage and understand it in making decisions. Scientists need to better align research and findings that allow A strong foundation of information allows us to build knowledge and a shared language allows us to communicate across disciplines. It’s a good start.

Hi Jason, Thank you for digging into this…absolutely imperative that designers gear up to play a key role in mitigation and adaptation. How many landscape architecture projects are even carbon neutral? Have you read https://www.lifeworth.com/deepadaptation.pdf? Would love to hear your thoughts.

Thanks Jamie – appreciate the thought. I have not read the paper you linked to but will take a look and let you know. Any other thoughts and resources that you know about please let me know.

JK

The paper is quite dark, but certainly gets at the urgency of the situation. Scientists are reluctant to become activists because they (probably rightly) fear being accused of bias, and the climate change problem is a perfect case for the emerging area of design research- great uncertainty coupled with the imperative for action. How do designers consider their role in climate activism?

Nice, Jason! I think OCCRI does a good job of discussing PNW impacts.

http://www.occri.net/ocar4

It is difficult to track all the models they look at, but they do a good job of summarizing seasonal impact ranges. It is alarming to look at and so good we are all incorporating this in to our every day thinking and design processes!

Looking forward to seeing you one of these days!

Yes, the latest Oregon Climate Assessment Report was the subject of a post a few weeks back – the OR specific info is great (although a bit disappointing that the bulk of their ‘report’ was attaching the PNW Chapter of the NCA4…) I’ve also been playing around with some of their models as well – good info!

Nice! I subscribed to your blog post. . . so hopefully I won’t miss these fun conversations and posts. Appreciate it.

Great! Yeah I didn’t want to bomb LinkedIn with posts every day, so subscribing is the best way, other than Twitter to get updates!