While not specifically urban, some reading worth your time is JA Baker‘s slim volume, The Peregrine. Written in 1967, it was one The cover of the 2004 edition I own features an introduction by Robert Macfarlane (who I learned about the book from via his readings). Seemingly simple in format, a short blurb from Amazon gives the idea:

“From fall to spring, J.A. Baker set out to track the daily comings and goings of a pair of peregrine falcons across the flat fen lands of eastern England. He followed the birds obsessively, observing them in the air and on the ground, in pursuit of their prey, making a kill, eating, and at rest, activities he describes with an extraordinary fusion of precision and poetry. And as he continued his mysterious private quest, his sense of human self slowly dissolved, to be replaced with the alien and implacable consciousness of a hawk.”

Although seemingly straightforward, the difficultly in describing this book starts early and you read simultaneously mesmerized and confused. Linear but mostly plotless, with only Baker and various fauna as characters, we are confronted with the sense that Baker is a bit off kilter, but that he channels that into an obsession so maddeningly pure that you are compelled to take his lead and head out into the landscape with a mission. The reasoning may be illness, as Macfarlane mentions that “he wrote The Peregrine following the diagnosis of a serious illness. This is never declared outtright in the book, but it is nevertheless made clear that the narrator is suffering from some deep wound…” (ix)

Macfarlane continues explaining the arc of the story as “non a book about watching a bird, it is a book about becoming a bird.” As Baker learns more about the birds and how to track them, as they are so fast you can’t spot them with the eye sometime, he discovers cues “that the peregrines can be located by the disturbance they create among other birds.” This immersion creates intimacy, and “By the end of the month, he has turned fully feral.” (viii-ix)

In fall this communion starts to happen in times when Baker identifies with the birds. A passive from November: “I found myself crouching over the kill, like a mantling hawk. My eyes turned quickly about, alert for the walking heads of men. Unconsciously I was imitating the movements of a hawk, as in some primitive ritual; the hunter becoming the thing he hunts… We live, in these days in the open, the same ecstatic fearful life. We shun men. We hate their suddenly uplifted arms, the insanity of their flailing gestures, their erratic scissoring gait, their aimless stumbling ways, the tombstone whiteness of their faces.” (95) The penultimate moment, after regular interactions through the winter, towards March:

“His eyes were fixed on my face, and his head turned as he went past, so that he could keep me in view. He was not afraid, nor was he disturbed when I lowered and raised my binoculars or shifted my position. He was either indifferent or mildly curious. I think he regards me now as part hawk, part man; worth flying to look at from time to time, but never wholly to be trusted; a crippled hawk, perhaps, unable to fly or to kill cleanly, uncertain and sour of temper.” (162)

I read fiction and nonfiction regularly, however, I read them very differently. Fiction is a focused and immersive experience, losing oneself in the story. Nonfiction, for me, is a learning experience, pen in hand slowly assimilating information to be used in the future. I started this book following the latter method, but in the end relaxed and lost myself in the narrative much like a fiction, . This was my experience, and it was at time perplexing, but in the end satisfying, again via Macfarlanes intro, this “is a book in which very little happens, over and over again.” (xii). Perhaps it’s the length that allows for this, as a book of this nature twice the size may be so ponderous as to be flung across the room at the mid-point. Multiple readings unlock different stories, so as many have pointed out, read it more than once, and each time you discover another hidden depth.

Thus instead of anything substantive, my markings became snatches of poetry, words and phrases

“Hill trees mass together in a dark-spired forest…

They layer the memory like strata” (9)

And

“The western horizon pricked out black and thorny.

Rain was coming.

Colour ebbed to brilliant chiaroscuro. (42)

From October 12th:

“Dry leaves wither and shine, green of the oak is fading, elms are barred with luminous gold” (49)

It’s the real joy, these drifts of poetry among what is at times mundane. You get the point, but this is loosely framed in the intro where it is less poetic and more prosaic, focusing on the habits and life activities of the birds (and lists of kills), along with a biography of the most common victims. Through this, Baker is understanding the actor in the landscape.

“The peregrine sees and remembers patterns we do not know exist: the neat squares of orchard and woodland, the endlessly varying quadrilateral shapes of fields. He finds his way across the land by a succession of remembered symmetries” (35)

At times he also tends towards being a bit more reflective, with statements like “Detailed descriptions of landscape are tedious. One part of England is superficially so much like another. The differences are subtle, covered by love.” (9). This is an important point about place, as Macfarlane mentions in the introduction, “Any writer who makes the English landscape his subject faces the problem of precedent. Each acre has been written about before… One way Baker effect this is to avoid official placenames. Instead he names his own place into being… He inhabits a cardinal landscape.” (xiv)

The passage that sums this is beautifully wrought, I imagine each of us describing our home place in such terms.

“A vivid sense of place grows like another limb. Direction has colour and meaning. South is a bright, blocked place, opaque and stifling; West is a thickening of the earth into trees, a drawing together, the great beef side of England, the heavenly haunch; North is open, bleak, a way to nothing; East is a quickening in the sky, a beckoning of light, a storming suddenness of sea…” (13)

In the Northwest where I reside, even in urban areas, Peregrine encounters are relatively common, and always exciting. The scenes in the book of behavior and hunting I’ve never encountered, and the bluntly poetic language of attacks and evisceration are intensely wrought, putting you in the space. This language and connection between man and bird is evident, and real because they require a deep immersion in the bird watching experience, or an obsessiveness I’ve not yet attained in my bird-watching.

For Baker, the bird and its plight itself was part impetus for the book, as mentioned on the J.A. Baker site: “In the mid-1960s when Baker was writing, the peregrine was under threat as a species. A build-up of the DDT pesticide in the food chain, of which the peregrine is at the top, led to weakening of their eggshells. Brooding of eggs was unsuccessful as the weight of the parents was too great for the shells. It was the possibility that this great bird might become extinct that influenced Baker to write his book.”

He mentions mid-way the winter, the stark reduction of numbers of overwintering peregrines, mentioning that “Few winter in England now, fewer nest here. Ten years ago, even five years, it was very different. Peregrines were seen almost every winter then…”. After listing a number of locations, he concludes, “These were the traditional wintering places, remembered and revisited by dynasties of peregrines, deserted now because there are no descendants, because the ancient eyries are dying, their lineage gone.” (116)

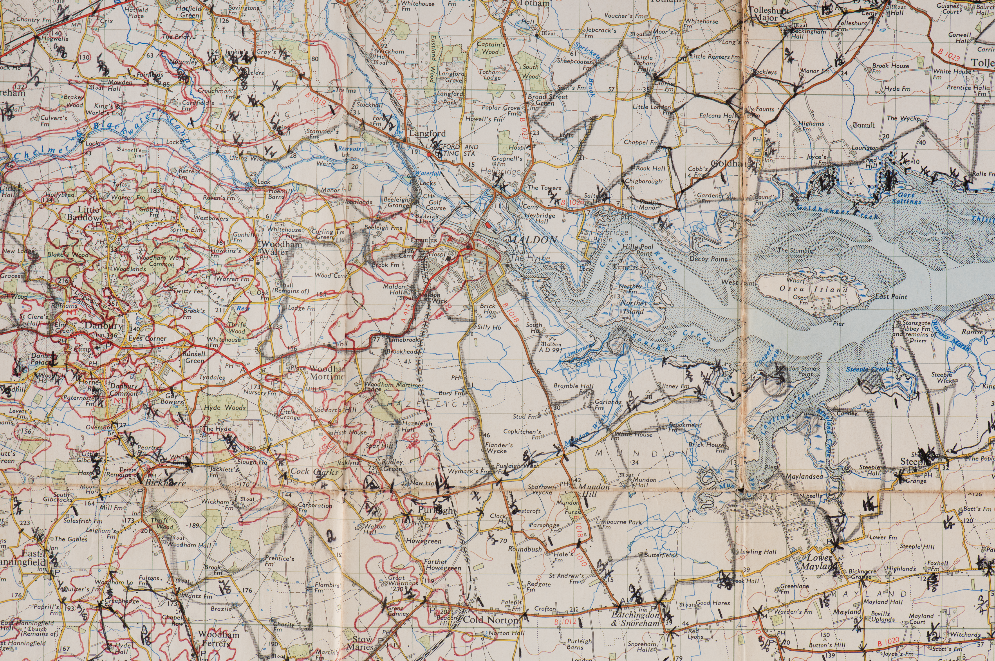

The annotated map (also in the header) is instructive, highlighting the relative small area of this study, but the attention to detail of behaviors and documentation. The study are was only 20 miles x 10 miles, allowing for a personal connection with the handful of Peregrines occupying this area.

While very tangentially related to both landscape and urbanism, it does have a powerful resonance in terms of the language of landscape, the presence of place, and the act of observation, looking, and understanding. Last year was the 50th Anniversary of the book was published, with a new edition and afterword by Macfarlane, and it continues to intrigue nature and landscape lovers of all stripes.

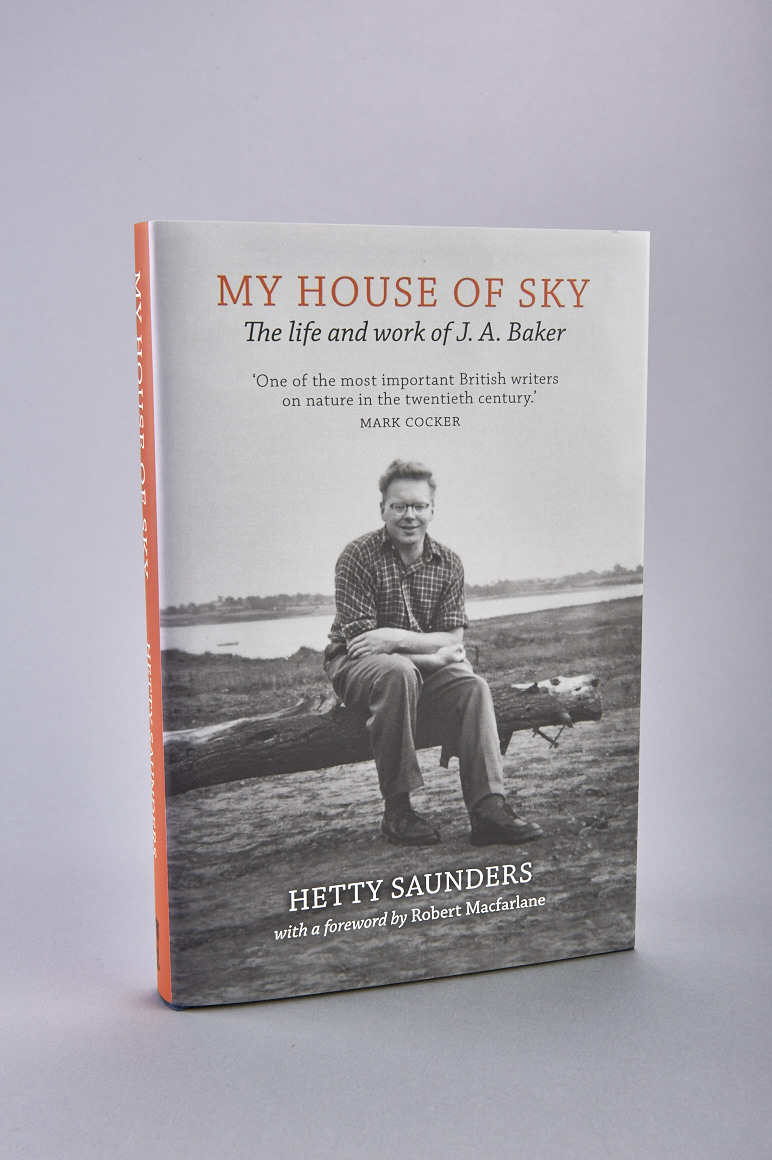

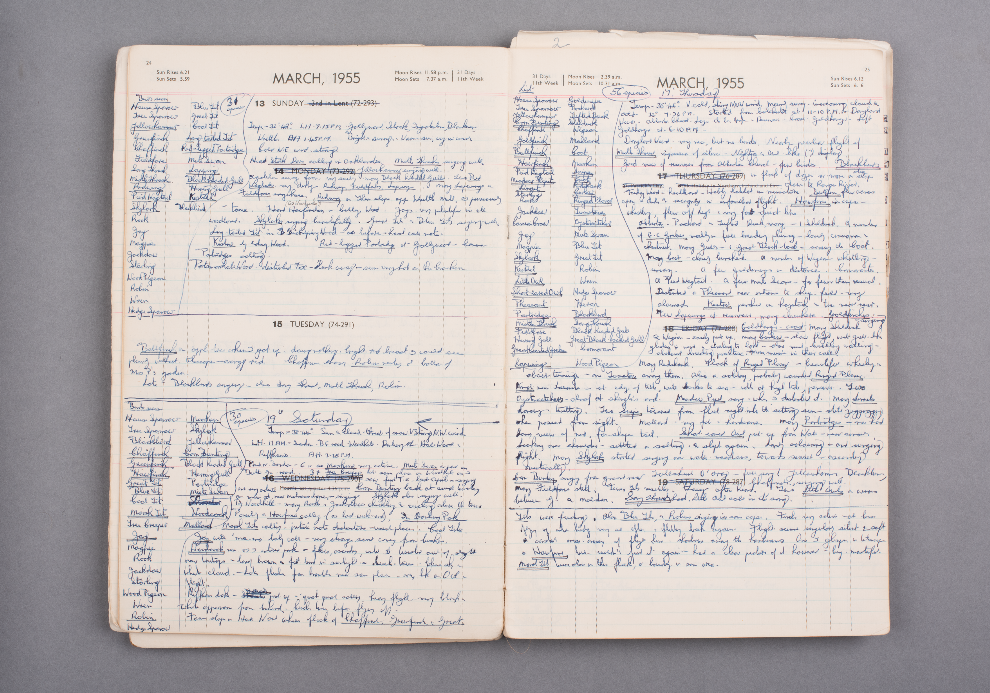

With the reading, one wants to dig in further, and it’s possible now, with a biography by Hetty Saunders, My House of Sky: The Life and Work of J.A. Baker, was published by Little Toller in late 2017. From their site: “‘My House of Sky’ is the first biography of the acclaimed and enigmatic naturalist, J.A. Baker, author of ‘The Peregrine’. and ‘The Hill of Summer’. ‘My House of Sky’ has a foreword by Robert Macfarlane and an afterword by John Fanshawe. Complete with many photographs from the new J A Baker archive of Baker himself, his notebooks, journals and annotated maps, this new book also has a photo essay of Baker’s favourite landscapes by Christoper Matthews, and original artwork by the stone carver Jo Sweeting.”

The Little Toller site (and I imagine the book) has some great imagery from Baker’s life, including his annotated map and notebooks, along with some of his gear. Worth picking up the book, and you may be compelled to learn about this life after reading the book.

A short video as part of the crowdfunding effort from the book, sheds some light on the biography here.

My House of Sky by Hetty Saunders from Little Toller Books on Vimeo.