I’ve posted previously about the LA+ Journal, which has had previous issues focused on both Wild (reviewed here) and Pleasure in previous issues. The current issue takes a radically different turn – with a focus on subjects around the broad concept of Tyranny. Perhaps a strange topic for landscape architecture journal to tackle, and I had that reaction a bit myself, but it quickly became clear that tyranny is a much more radically complex idea than what comes to mind, and the social, economic, and spatial manifestations have direct relevance on urban spaces, their design, and their evolution.

“From the first utopian impulse of Plato’s Republic to today’s global border controls and public space surveillance systems, there has always been a tyrannical aspect to the organization of society and the regulation of its spaces. Tyranny takes many forms, from the rigid barriers of military zones to the subtle ways in which landscape is used to ‘naturalize’ power. What are these forms and how do they function at different scales, in different cultures, and at different times in history? How are designers and other disciplines complicit in the manifestation of these varying forms of tyranny and how have they been able to subvert such political and ideological structures?

LA+ TYRANNY asked contributors to consider how politics, ideology, and technology manifest in our landscapes and cities in ways that either advance or restrict individual and collective liberty.

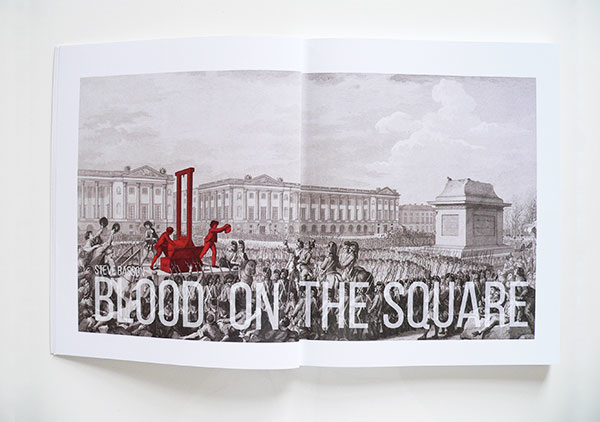

The unique lens of tyranny is understood in recent cultural context early, in the essay ‘Blood on the Square’ by Steve Basson (8). The concept of the square as free and ‘democratic space’ indicative of the historic connotation of the Greek Agora ‘political debate’ and at times the locus of “heroic protest” as seen in the US and abroad is contrasted with the square as a historical place for terror and exercising of oppression. Examples of these public spaces being used for public executions, propaganda and military force, as well as new levels of surveillance through CCTV and policing and other means evokes dystopian visions of Bentham’s Panopticon and Orwellian visions of Big Brother.

The space, like any others, is available for both freedom and repression, and that a ‘pure’ public space is a myth. As referenced by Foucault, the history of the public square as exceptional or positive is built on subjugated knowledge “…where historical contents have been buried or masked in order to preserve the privileged nature of a particular narrative.” (12) The takeaway is that the square is not purely heroic, but is a ‘contested terrain’ and one that “… is virtuous and democratic but also grim and menacing.” (13) It also means that our power as designers is limited, because it is a dubious assumption that spatial organization could be employed to shape use in certain ways, and thus architecture and design “cannot create freedom in space” but rather from Foucault again:

“I do not think that there is anything functionally, by its very nature, absolutely liberating… the guarantee of freedom is freedom.” (13)

The theme brought up the previous essay is echoed in two subsequent writings. First, Gandy’s “The Glare of Modernity” (15) explores some of the power dynamic through the tyranny of lighting, which has been employed as a “means of intimidation and control,” and has now become synonymous with ‘safety’ to the detriment of livability and health through ubiquity. From a political perspective, Chang Tai Hung’s “Tianamen Square: The Grand Political Theater of the Chinese Communist Party” (20) explores the history and spatial configuration of this enormous public space in Beijing. While ostensibly the ‘People’s Square’ the narrative is more relevant to use of propaganda and designed with a focus on spaces not of comfort (no trees, benches) but of immensity and political power, referencing the communist “…contempt for leisure activities of the bourgeois…” while also avoiding the potential for spaces to be “subversive gathering spaces.” (22) The events there are then not people-driven, but “highly orchestrated” and a spatial equivalent of “a scripted text” (24) where those in power fear the unscripted.

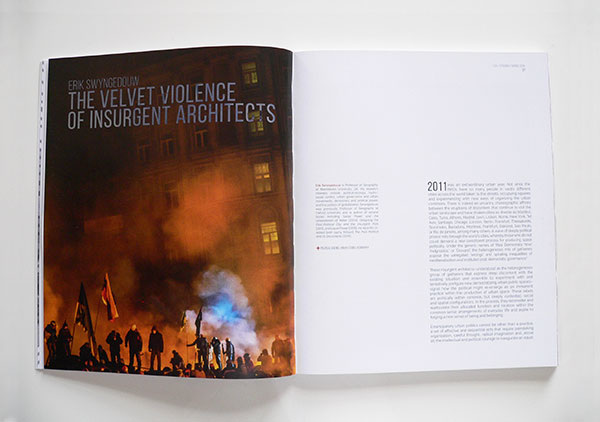

A common theme arises around the activities of the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement where places like Tahrir Square in Cairo, and Zuccotti Park in New York became well known, among many others as significant places of occupation and protest. Erik Swyngdouw’s exploration in “The Velvet Violence of Insurgent Architects” (27) looks at these places of political protest and the participants as “radical imagineers” of a new urban future that can include spatial policies of planning, architecture, urban design against powers that are averse to disturbance. (28) The concepts around the Right to the City movement (both formal and informal are realized in these “tactics of resistance” (29) and that these insurgent architects become designers of a sort:

“While staging equality in public squares is a vital moment, the process of transformation requires the slow but unstoppable production of new forms of spatialization quilted around materializing the claims of equality, freedom, solidarity.” (30)

Another reference to the Arab Spring is from Mona Abaza’s “Memory and Erasure”, (32) which looks again at Cairo, Egypt but through a different lens of public / political art complementing the occupation of public spaces. The process of art being used as part of protest, and the subsequent painting over by authorities was a subtext of the larger power struggles happening within spaces throughout the cities.

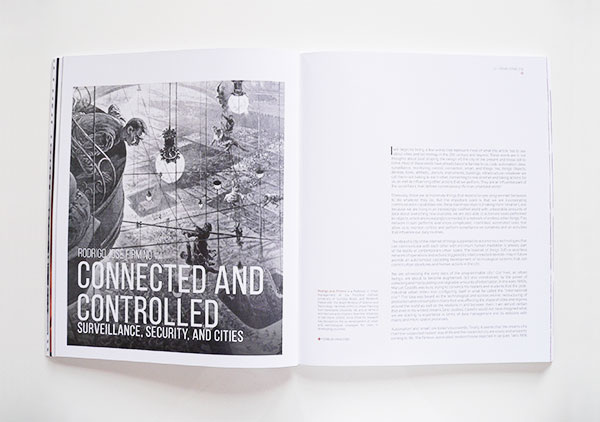

Rodrigo Jose Firmino explores technology in his essay “Connected and Controlled: Surveillance, Security and Cities” (42) which looks at a more pernicious tyranny that effects most of us. Expanding on Castells notion of the “informational city” with new technology and the Internet of Things, the essay posits a “Programmable City” where data is not just captured but utilized – taking advantage of the ubiquity and our reliance on smart technology to exert levels of control never before seen (with the exception of films like the Matrix and Minority Report). (44)

The appropriation of space by those in power through technology can also be utilized by the public who can be “empowered by the same kind of technologies that be used to destroy their liberties,” expanding on ideas of crowdsourcing, pop-up, or DIY cities. (45) Our living in the “maximum-surveillance society” means that these data are the most “powerful commodity in the informational smart city” (46) and become methods of control under the guise of safety, while also blurring lines between public and private spaces, ultimately concluding that Smart Cities perhaps lead more likely to dumb citizens.

Taking the idea presented above for appropriation of the tools of those in power to fight against that power, Stephen Graham’s “Countergeographies” (55) provides a framework for complementing the traditional methods of protest with new ideas of “Cartographic Experimentation”. A number of examples are explored, falling into categories of Exposure, Juxtaposition, Appropriate, Jamming, Satire, and Collaboration, the essay provide multiple ideas of new ways of engagement that are more “emergent, fluid and pluralized.” These experiments are useful but limited, as the author mentions, because of their lack of legitimacy – as art and activism versus being mainstream and political, but that a new wave of activists can adapt and expand them into the lexicon of more traditional forms of protest.

A historical path taken by Fionn Byrne in the essay “Operational Environment” (62) touches on some of the military roots of site design, including Le Notre and Vauban’s spatial reactions of “ballistic trajectories” (64) and the more modern appropriation by landscape architects and planners of military aerial imaging for analysis and ecological planning ala McHarg and modern GIS. This reduction of landscape and environment to “quantifiable data” as referenced by Waldheim leads to a methodology for militaristic problem solving, where “The force of the military’s technological, informational, and industrial apparatus is being set upon the environment, reducing nature to both a resource as standing reserve on the one hand and a technological-controlled, environmentally managed set of ecosystems on the other.” (66)

A more site specific and compelling examination relevant to design in many was is the essay by Patrizia Violi in “Traumascapes: The Case of the 9/11 Memorial”. (70) Taking one of the most visible examples of memorial in modern history as point of departure, Violi wonders the role of these places in “constructing, transmitting, and defining a collective memory,” and using the metaphor of memorial as text to show how

“historical memory is not something well defined once and for all, but rather something that is changing continuously over time. The actual events themselves are remembered differently, according to the different discourses, texts, images, symbols and gestures produced in relation to them.” (72)

Which is perhaps the dilemma of the legibility of any space, especially ones by which interpretation is a key element, telling a story requires framing (spatially and as a narrative) the elements of what are important, but also set up a sequence and path in which the story is told. Using the 9/11 memorial and the chasms created by the designers are indicative of the idea of Index, as referenced to Charles Sanders Pierce, in which “…a sign that exhibits a direct, causal link to the actual event that produced the sign, and which the sign itself, in its turn, signifies.” In this way, using the voids of the towers and their “material traces of the past, with direct spatial links to it, and this endows them with a very unique type of meaning.” (73)

While the potential is there for connection of space and event, it is much to ask, the social and cultural functions of ‘trauma sites’ are more indistinct, as the author concludes: “We cannot expect a memorial to capture the complexity of an event of this magnitude, or account for the whole chain of events that follow the initial principal trauma” (75)

This is also echoed by Nicholas Pevzner in “Trees and Memory in Rwanda” (78) where he connects the forest and remnant trees as symbols of ecological devastation, war and economic disasters throughout the country. In particular the unintended memorialization a the Umuwmu tree, a species of Ficus that were typically planted near houses and are sacred. These lone trees and groves left now are reminders of houses burned down through strife, a subtle way of remembering past, “symbols of atonement as well as victimization” (81) Another poignant example in the essay was the use of trees in conflict between the Israeli people (who plant pine forests on lands in attempts to claim land) and the Palestinians who plant olives to mark ownership. The battle of lands plays out in Israeli’s bulldozing Olive groves, and Palestinians using arson to burn pine plantations. Both stories show the role of landscape not as innocuous field of war, but as part of the strategy.

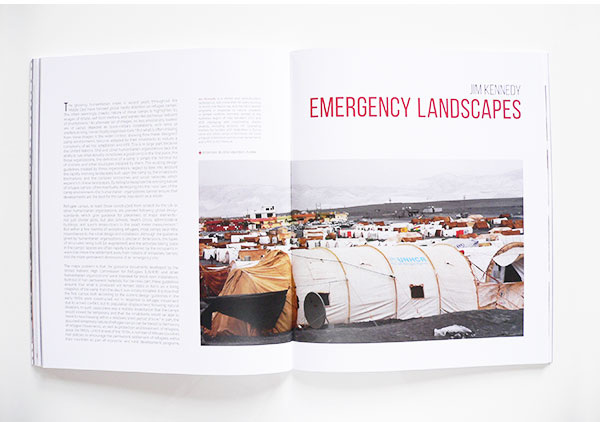

One of my favorite essays was an enlightening take on the structure of the refugee camp, ‘Emergency Landscapes’ by Jim Kennedy, (84) who is a shelter and reconstruction professional, and his experiences with informal settlements. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) establishes guidelines for these camps, but “neglect to take into account the rapidly evolving landscape built upon the camp by the inhabitants themselves, and the complex economies and social networks which expand into these landscapes.” (86) The quidelines themselves were designed for short term (natural disasters) but are insufficient to handle long(er) term occupations of many months or years, which is more common in areas where armed conflict makes early return impossible. So residents have taken the blueprint and using the “malleable materials” people “build barriers, food stalls, paths, roads” and other spaces.

This process is not always democratic or ad hoc, but is often used to create power dynamics with camps of the haves and have-nots, with processes that limit access, create walls and other enclosures to privatize spaces, and create better conditions for some at the expense of others. Without an “idea of what is a good camp” the question of these longer-term occupations will always be fluid, and Kennedy sees a role for landscape architects in both analysis through observation and research of the morphology (shape), operations (use) and performance (good or not?) of these spaces, as well as to establish and “inform incremental, cumulative, and mosaic approaches.” (89)

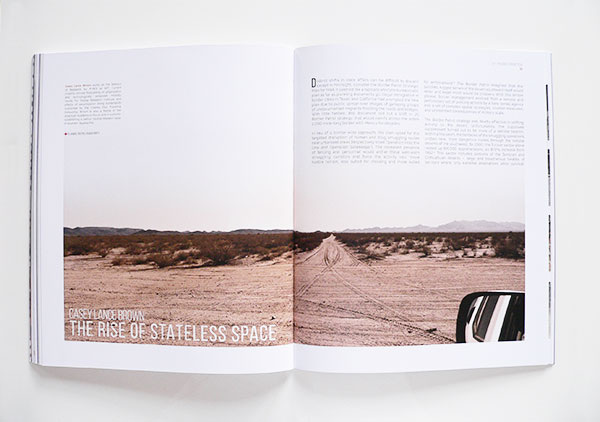

‘The Rise of Stateless Space’ by Casey Lance-Brown (92) delves into the amorphous “pockets of absence… where the rule of law is questionable,” those “contested spatial zones [where] the normal laws and standards of protections no longer apply.” (94) Using the examples of Border Patrol zones in Mexico, the focus of policing certain zones against smugglers, which moved illegal activities to more hostile and remote areas, which led to more deaths and also more extensive ecological destruction, disruption to wildlife, and other impacts. Layers of “spatial ambiguity” (96) can be smaller scale or global, with DMZs and contested territories, but remind me of further readings on Heterotopias and Terrains Vague, that expand these notions and provide interesting perspective on the role of the state and the variety of interactions with less control that are compelling to thing of in terms of emergent urbanism.

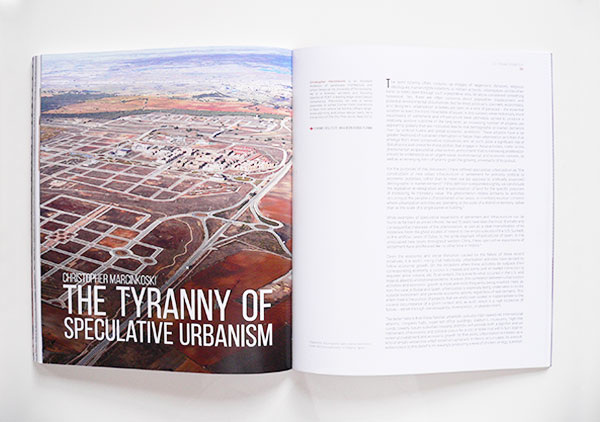

Some final essays I thought were less engaging, including a rather flat book review of ‘Architecture and Armed Conflict’ by Nick Mclintock (100) and ‘The Tyranny of Speculative Urbanism’ by Christopher Marcinkoswki, (104) where he makes the case that tyranny exists in the development of speculative urbanization due to the exploitation of ‘vanity pursuits’ through real-estate developments. Through examples, many from Africa, he shows that typically urbanization is often regarded in a positive frame as growth (good), however, it is used in nefarious ways in not really creating places of real worth but as a way to generate capital or to generate global competitiveness instead of addressing real issues that regions should be focusing on. While it is clear that urbanization is not neutral, this isn’t really new ground on which to tread, as criticism of misguided eco-cities has been kicking around for a while, and green inspired development for even longer. In concept it is somewhat interesting, but the essay itself doesn’t really come together beyond a few examples, nor did it really elevate to the magnitude befitting the tyrannical.

On that same note, after reading the collective works, the closing essay ‘The Innocent Image’ (114) where Richard Weller offers a cranky argument about the overly photo-shopped project imagery, comes off as tired, and also doesn’t really fit the frame of this issue in terms of focus. The tyranny of ‘Planet Photoshop’ doesn’t match that of the urgency that the rest of the journal holds.

The wide array of voices that are not typically part of landscape architecture discourse is perhaps the best part of the journal. I kept a list as i was going, and the diversity includes geography, architecture history, humanities, sociology, urban management, semiotics, art, urbanism as well as landscape architecture, to name a few. It’s a type of dialogue that is outside of the landscape architectural mainstream (with the exception of academia) and it’s good to get perspectives I’d equate more to a broader Urban Studies focus woven into LA discourse – reinforcing the plus of the LA+ brand.

A series of illustrations woven throughout the journal that explored a variety of topics in visual form – which although sometimes interesting, did little to add to the content in meaningful ways. Aside from that, some may struggle to find the links to practice of landscape architecture, and there are definitely a few essays that maybe float to those fringes, but most included illuminate a multitude of perspectives beyond theory and provide solid fundamental issues relevant to practice. And that is what a journal should do, ably demonstrated by LA+ as it has emerged, now the third issue, as a unique voice in the landscape architecture and urbanism discourse. This one is a dense read, but compelling and relevant.