I’ve mentioned a few times on Twitter, I have had an on-going interest in game design as a medium, but also in relation to the potential synergistic overlaps between the technology/techniques with landscape architecture and urbanism practice. The most obvious connection has to do with visual representation, as the ability to create engaging site and building environments is clearly , but there are some interesting opportunities for educational tools, user experience, ecological and urban modeling, scenario building, and iterative design.

ORIGINS

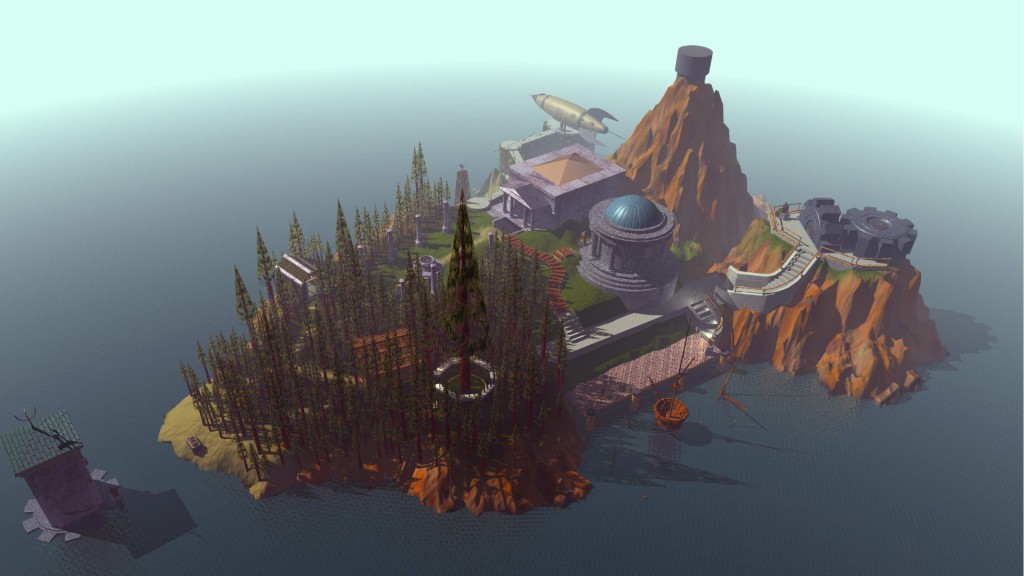

Growing up with gaming, a trio of interactions early in college defined the concept and hooked me into the potential in an interesting way – even 20+ years ago. The first was a game my sister and i were obsessed with, Myst. Building on the word-based computer games from the 80’s like Adventureland and Pirate Adventure, Myst came out in 1991 and provided a graphical environment (that at the time was incredible) along with a mystery and things that needed to be observed and unlocked.

The interactivity and lack of linear timeline, which included puzzles and problem solving was great for some obsessive teens, but showed that games didn’t have to be either violent or proscriptive. The follow-up Riven in 1997 had better graphics and another story.

The second was for a urban planning class, we were giving a quarter long Sim City game simulation and discussed progress in class, as a way to explore ideas. Those of the certain age will appreciate the 2D top down version of Sim City, as we were doing this initially in 1993:

The scenarios allowed us to employ principles of urban simulation, think through the concepts, and then starting the clock and see how things evolved, or more likely devolved. To use this for class was transformative. The graphics have come a long way, indeed, since then, as this recent Sim City graphic below shows, with the more prototypical 3D Axonometric we think of with the game.

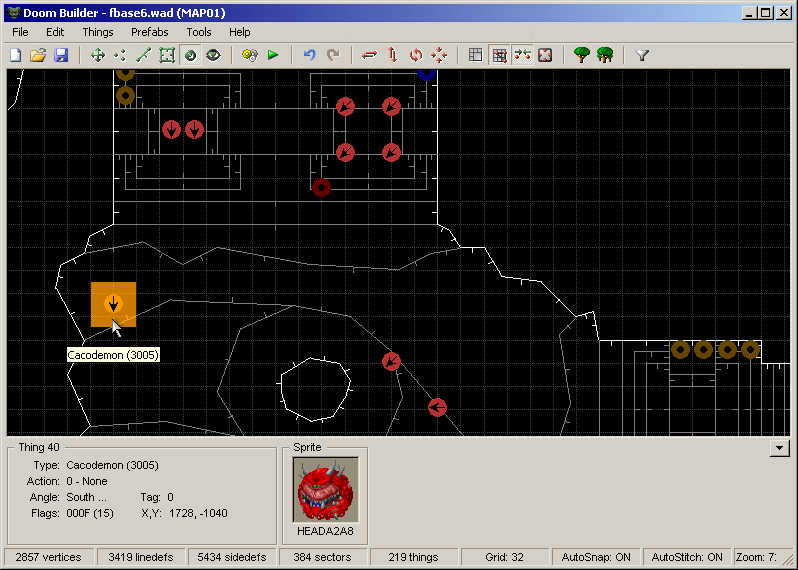

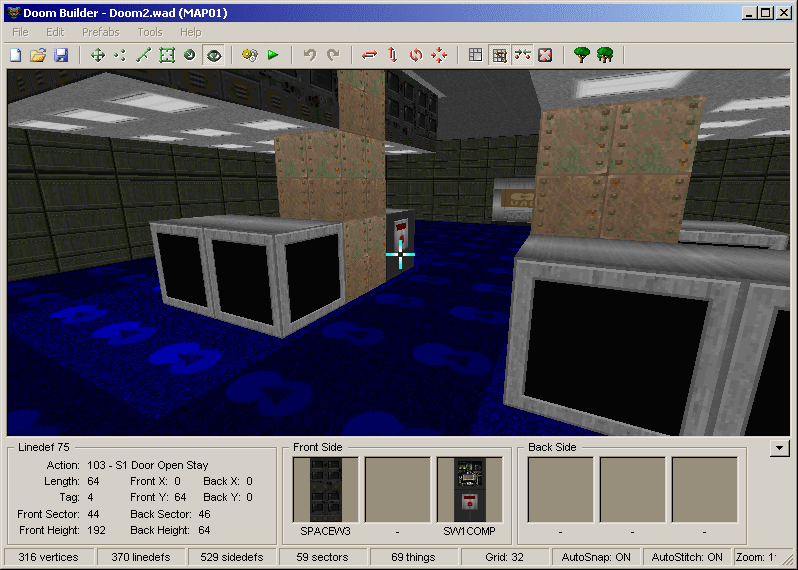

The technology seems akin now to some of the less game and more GIS specific tools for scenario-building in programs like ESRI’s City Engine (more on that that and GeoDesign here). On the flip side of the Sim City was geeky kid favorite Doom, the immersive and ultraviolent 3D game that literally and figuratively blew away gamers at the time.

In addition to an addictive, networked game play, there was an added feature of a back end tool to create worlds Doom Builder – which paired a bit of Dungeons and Dragons graph paper mapping with rudimentary 3D graphic world creation. The difference of course is, once done with the creation, you could play your creation.

THE SOPHISTICATED BEAUTY OF GAMES

It’s easy to dismiss gaming as a medium for geek culture with little relevance to the lofty ambitions of the architecture/urbanism endeavor. But there’s a lot more to it that shooting thing and bloddy violence. As shown above, there’s potential for wonder and problem solving, urban planning education, world building, and yes, lots of bloody violence. Guess it’s a good metaphor for life, right?

But, the ubiquity and size of gaming culture goes beyond a few teen to twenty-somethings playing violent FPS games. The size of the industry is worth billions. And that revenue is diverse. The demographic for the prototypical first person shooter is probably more focused, but there are men & women, young and old, across races that participate in some what in gaming culture.

The few recent games that have blown me away recently provide some context. First, the simplicity and beauty of Monument Valley – as probably first seen on House of Cards, which in addition to fictional presidents, appeals to designers and architects (especially those with a fondness for Escher), with atmospheric graphics and more literally puzzles to solve. The games are challenging enough to engage but not so hard as to frustrate. It’s a lot of magic.

Shifting gears to more modern FPS games, one of the first games i discovered in recent years was Bioshock Infinite, a much hyped and controversial game that wove through a fictional universe of a floating city of Columbia on a quest of sorts. Atmospheric and with a great, detailed backstory, the legend that the game exists within is compelling. The graphics complements the narrative with quasi-realism and a fuzzy, dream like quality.

The predecessor Bioshock also had an amazingly creative environment, which in converse to Columbia City was the underwater city of Rapture lending to a more moody and claustrophobic emotional state.

Both of the Bioshock games are, as well, incredibly violent, which takes away somewhat from the exploration and appreciation of scenery, but makes for some excitement.

A beautiful game in terms of the subtle environment is the graphic but non-shooting murder mystery, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter. The player wanders through a landscape and abandoned town to find clues and unlock the secret of what happened. It’s emotional and you feel it, the scenery and soundscape lending to the drama.

As images, these don’t do justice to the feeling you get from these environments, which have subtle motion and great mixing of ambient sounds. For anyone new or interested in gaming, who wants to experience what a well crafted, non-shooter, modern game can be, this would be a good one. I included a video so you can see the experience:

For me it’s not a stretch to jump from these narrative stories to having the ability to explore a project site or potential design. I see the above image of the rail tracks, and immediately it evokes a simulation of exploring the High Line, both before and after construction. And not just exploring, but interacting, seeing motion and complexity. With simple visual cues This game evokes that feeling.

Finally, a more recent game released in installments is Life is Strange, which follows a third person graphic adventure of a teenage girl in an odd Oregon town. She is able to unlock events by rewinding time, which allows you to make different decisions and see how that impacts outcomes.

Check out here for more on the plotline, but the graphics again reinforce the mood. It also offers a slighly different game interaction, with a sketchy white line graphic that appears when something is of note either on the object or as subtle cues. I also love in this case there’s a proto-realism – it’s got a tinge of cartoon to it, but is also brilliant at capturing mood and the mundane.

The sophistication of these games in terms of environments, aesthetics, and narrative draw you in. There’s not a feeling of immersion, although i’d love to see some of the graphics in a VR rig, but your are 100% immersed in both the story, and, when it doesn’t get in the way, the graphical interface, also known as the HUD, or human user interface. It’s a big deal, this interface, and millions have probably been spent on making it seamless. While specialized controls and rigs are used, they are available to a few. For most, there’s simple touch or mouse input, whereas the line between the user and environment is very distinct.

A game, of course, is a constructed world with a narrative already baked in. And there are likely many more examples out there that make the point that games can be both defined broadly and offer a very close connection to the world building of landscape architecture and urbanism. While it’s possible to offer free movement and discovery in these games, in the end there’s a series of tasks, events, actions required to move from start to finish. It’d be a dull game indeed where you just walked around in an environment with no purpose.

That said, the approach may be different, and the way the environments are used may also vary, but the fact is that these games give visual examples 1) constructed worlds, 2) the ability to freely explore these worlds, 3) animated objects that also exist in these worlds, and 4) a measure of emotion and mood that is derived from real environments and landscapes. In this way, they become similar to visualization in a design medium. Thinking of this less as a narrative

TOOLS

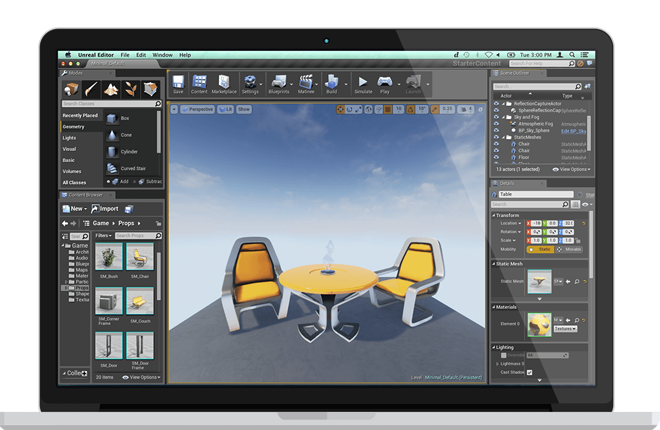

There are many tools out there focused on game development, all of which blend tools for creating environments, coding behaviors, and developing user interface. The one I’ve spent the most amount of time working with is Unreal Engine, which is amazingly, now a free to use suite of tools (with a royalty structure set up to capture revenue). An example of the tool in an architectural setting, is the Unreal Paris, a video tour that came out a year ago, showing a highly photorealistic scene done in Unreal Engine, which shows the level of detail that is typically available in static rendering now being employed in a space that is both fully 3d and fully interactive.

It’s a bigger stretch to expand this beyond the enclosed architectural space, and delve into the landscape. The complexity of materials and motions in the entire apartment is probably less than a single tree, thus, to me, this is the holy grail. The seemingly large gap between architectural rendering and landscape is immense. However, this is changing. To see the potential of the technology, Epic Games did a very impressive video on their ‘Kite Demo’ seen below.

It’s a really nice animation, akin to a Pixar movie, with some stunning visuals. The part that’s not evident is that this environment is a fully realized world, which you could right now, dive into and be able to explore every square inch, through multiple platforms from game systems and virtual reality rigs. The concept that it’s not just a static, linear progression, but an actual, virtual world, is the wow moment. Because, as a landscape, while not perfect, it’s head and shoulders about anything i’ve seen in 3D landscape architectural visualization. The level of detail and size of this world gives you a taste of the potential for landscape to be transformed by these tools.

While the demo itself is impressive, if you want to dig into the specifics, there’s a longer demo from GDC 2015 that goes in-depth in some of the technology uses to create the demo assets and put them all together. It’s geeky, it’s technical, and it’s amazing.

As shown, there’s a strong visual component to this type of work that fits nicely into landscape architecture production, but it’s interesting to think of some uses that expand the notion and potential for exploration and movement. The potential for specificity, as you see with the second more detailed video, isn’t relegated to a generic library of materials, but can be augmented with a range of scanning and capture tools, such as detailed photogrammetry that yields highly realistic assets.

There’s a healthy competition between game engines, with Unity competing with Unreal Engine for pros and amateurs alike, with companies adapting or creating their own engines to fit, and a range of other free and adaptable tools based on what you like and your goals. As i mentioned, i spent time with Unreal Engine mostly, but all of them have pros and cons (in terms of horsepower, learning curves, etc) – and technology is vital to this as i found out, as i could do some basic world creation and programming, but soon found my older desktop puttering with the high graphic demands. Be forewarned, this doesn’t just open up on your current machine and go, there’s potentially an investment of time (in training) and resources (in techology) to fully unlock the potential.

The beauty of all of these systems (which are all similar in features with some variations) isn’t just the end result. The high graphic quality and immersive end result that is nimble enough to run in real time is seen in the game examples above. The tools are very sophisticated, with the ability to import and manipulate 3d assets from other worlds, create new assets, locate and building ‘levels’ in game parlance. With libraries of elements and compatibility with other programs like Maya, Mudbox, etc. (SketchUp is pretty tough to get to work though).

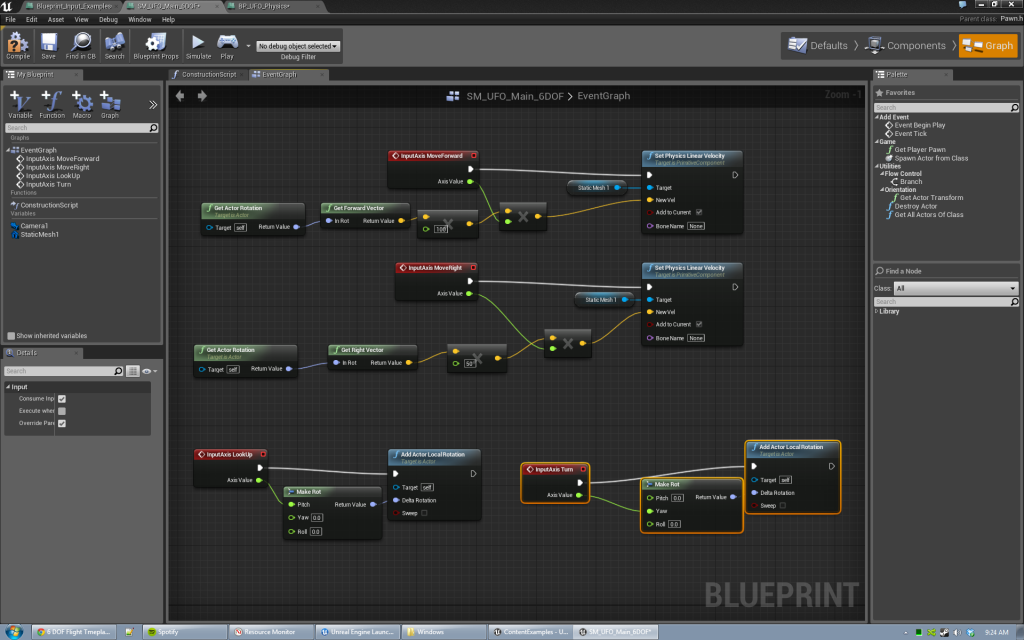

The back-end is where there’s a lot of beauty, with the scripting language and programming adding the dimension of interactivity to the environments. As you see below, the Unreal Engine uses a feature called Blueprint, which is a scripting environment that is based on automation of the C++ code, and is useful for non-programmers to be able to literally connect the dots on to create triggers, interactions, events, and other ‘life’ to the scenes. At a simplest level, you can take an object and give it action, such as the ability to turn on a light when a character gets within a certain distance, or to trigger sounds, or have other character’s act. Any action can be scripted in a non-linear, interactive way to create sophisticated environments.

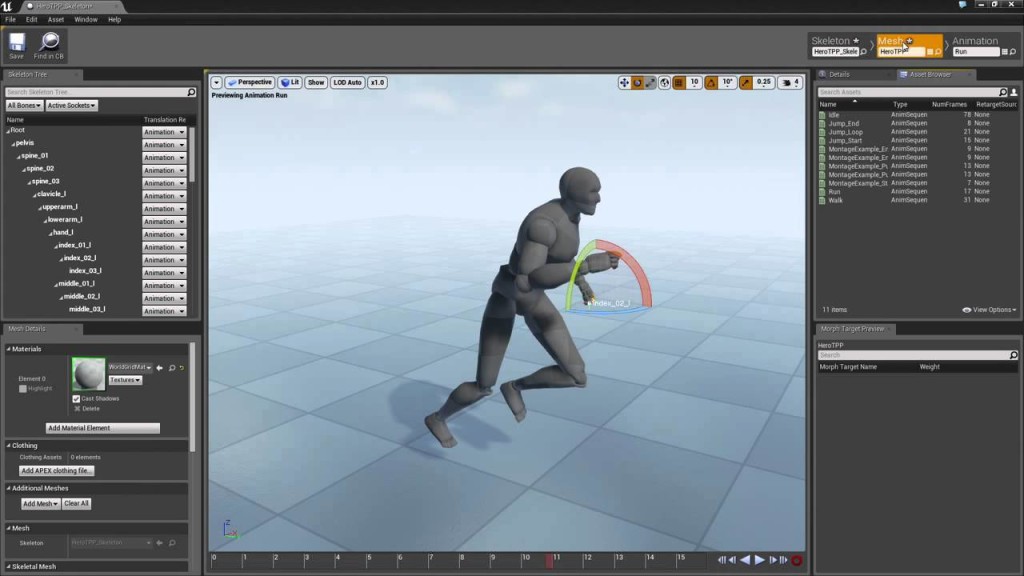

And the specific elements for rigging characters, which can be added as main characters, either people that you can interact with, or imbuing more lively entourage into a scene.

Admittedly there’s some lag in the quality of these, as we’re far from life-life, but they are much improved. Call it more Pixar than reality but with a lot of interesting gestures, facial controls, and the ability for lifelike actions.

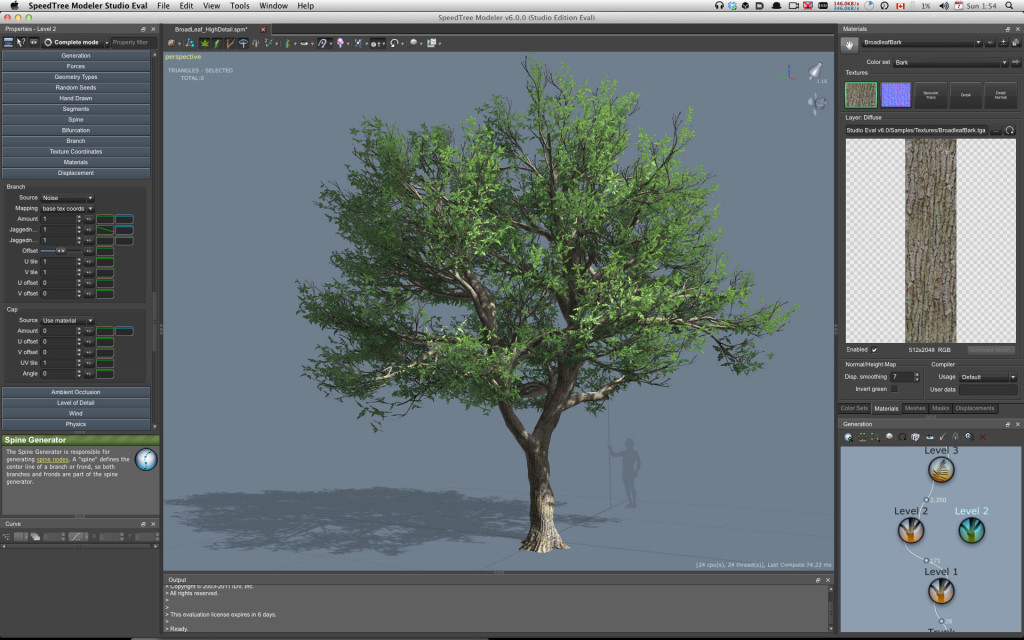

In relation to landscape, another worth discussing is Speedtree, who creates cross platform vegetation for gaming as well as film (hell, they just won an Oscar!). The tools allow customization of every aspect of trees, both in off the shelf libraries (which i’ve used) and a custom editor to create any type of vegetation (which I haven’t used, but is compelling). Gone are the days of cartoony vegetation, and the sophistication of the algorithms allow these to render in high quality and even incorporate wind, lead drop, and more w/o draining graphic resources (as also discussed above in the Unreal GDC video), something that high poly count vegetation seems to persistently be problematic.

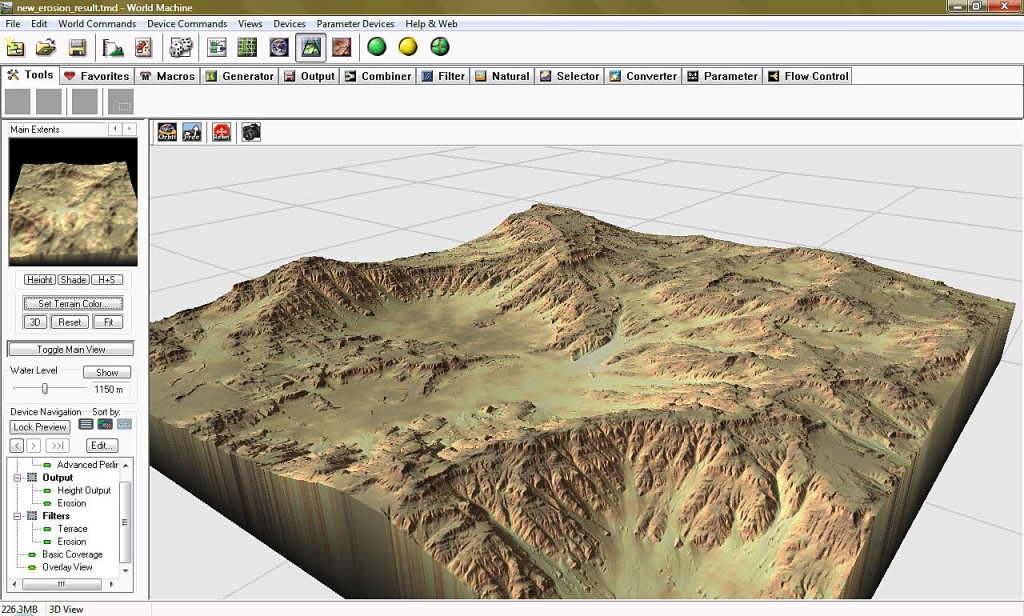

Jumping out a scale to the overall terrain, the ability to create specific context is key to creation of these realistic environments. One that i used a bit is World Machine, a terrain modelling program that allows you to import topography from existing digital elevation models (DEMs) as well as to create custom features, and integrate geologic phenomena such as slides, erosion from wind and water, and other features.

These help by providing distant terrain that interacts with the other more close up assets along with sophisticated ‘level of detail’ or LOD settings that provide realistic close up information, including motion, then slowly stepping down resolution in levels, as the view gets further away. The addition of atmosphere and really amazing lighting tools, adds to the perspective focusing and gives depth as well as life to scenes. This allows for efficient use of computing resources to but the action where its most needed. The results are simple but stunning.

Another one i that i learned about more recently is Lumion, which we use at my office. I’ve seen some of the renderings but haven’t dove into using it myself, but it seems to integrate with much of what other game engines do, and perhaps more seamlessly. It is based on game engine technology, but has the added advantage of being focused on architectural visualization with tools to integrate directly with industry standard Revit.

A short video shows how it works.

And some of the results:

FINAL THOUGHTS

So as you seen, even in this short snapshot, there are a ton of resources, and many more i don’t know about of haven’t covered. This brain dump of a lot of ideas that definitely could use more exploration, but i wanted to close out the thought by giving some context on why i think all this, geekery aside, matters. The takeaway is that there is a ton of potential to disrupt and expand practice, if we can expand methods of visualization and adopt some of these techniques. On that note, a few thoughts that are worth further exploration:

- Immersive technology, utilizing controller and VR rigs to allow clients and users to experience the design in a number of ways, while also allowing designers opportunities to fine-tune spatial relationships and test environments.

- Rules based ecological scenarios, which allow for natural processes (vegetative colonization, competition, dispersal) that provides simulations of open-ended landscape concepts.

- Topical games to create better understanding of system interactions and engage larger populations, such as stormwater, infrastructure, climate change.

Have thoughts and other examples and stories, or know of folks in the industry working and using these tools? Let me know.

Hi Jason, this is a great review of some of whats available. I especially like the 3 closing points on your “brain dump” and feel that there is a lot of room for exploring and representing the world that is not just “out there ” but also “in here” in the way that books, games and to a lesser extent movies create a interior personalised space through which we emotionally experience the environments we interact with. This is missing from the static photoshop renderings of an idealised future that are portrayed in the current landscape standard views. This is probably why some landscape architects nostalgically are harking back to the handmade drawings that they learned in studio, but games, with their dark and grungy, somewhat dystopian atmosphere could provide a different , possibly more realistic perspective to visualising and representing the future we are trying to portray, especially for us as users, but even more so for those disciplines that are locked into an ideologically based idea of what the world should be like, rather than the open ended mystery that real places allow us to have and that are largely missing from our commercialised and controlled urban landscapes, the cities we live in that make us sick, hungry and unhappy.