I recently gave a talk at the great annual conference Urban Ecology Research Consortium of Portland/Vancouver (UERC), which focuses on ” advance the state of the science of urban ecosystems and improve our understanding of them”. I was really excited to be chosen to present (i had done a poster presentation in past years), and it seemed a great way to introduce the Hidden Hydrology of Portland and what work has been done to date.

Much of this has been covered on the L+U blog – but there’s new ideas worth exploration, and some new momentum to realize some of the site-specific installations discussed here. A short visual recap:

Background

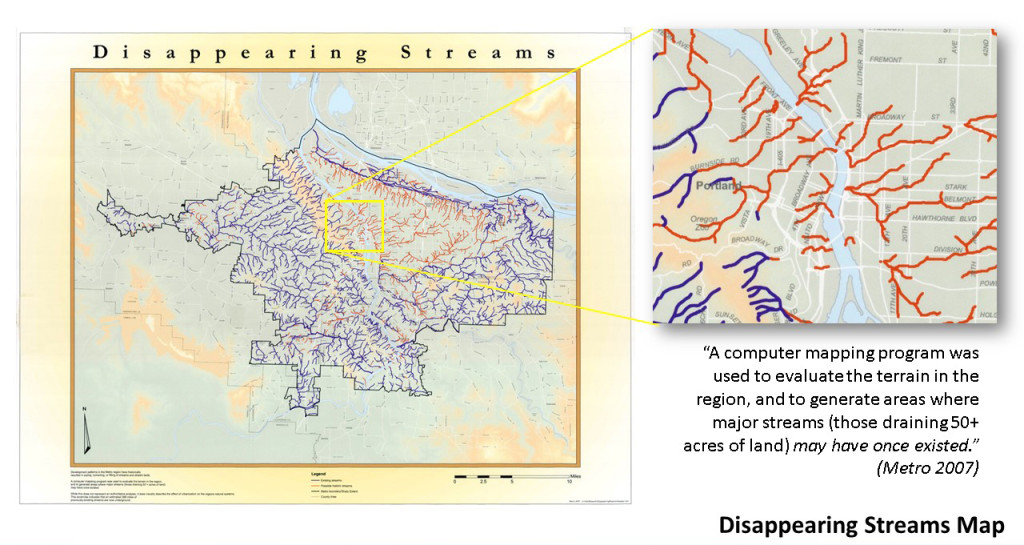

My first experience with the concept was stumbling over the ‘Disappearing Streams’ map produced by Metro. Not sure of the vintage – but I remember seeing this easily in the late 1990s, and it’s stuck with me for years. Not actual streams but modeled topography generating basins – the concept is pretty simple – show what streams existed, and highlight those buried, piped, channeled in red, which is predominately on the inner east side and downtown.

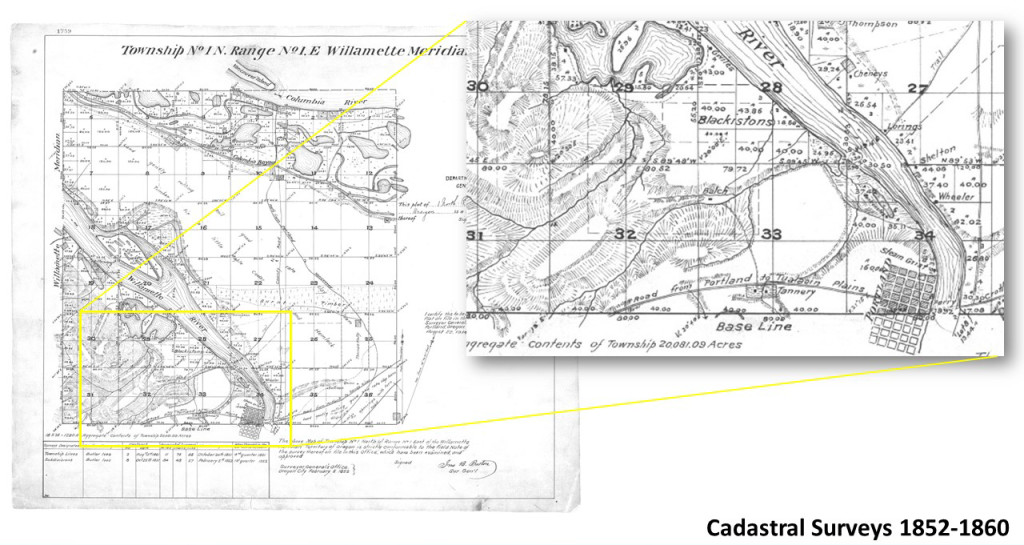

A bit of digging yields a great set of maps, the Cadastral Survey of 1852 provides amazing detail of a nascent Portland, with stream corridors like Tanner Creek still intact running through downtown Portland, and other ecological resources (wetlands, lakes) as well as trails and early city grid (seen to the right)

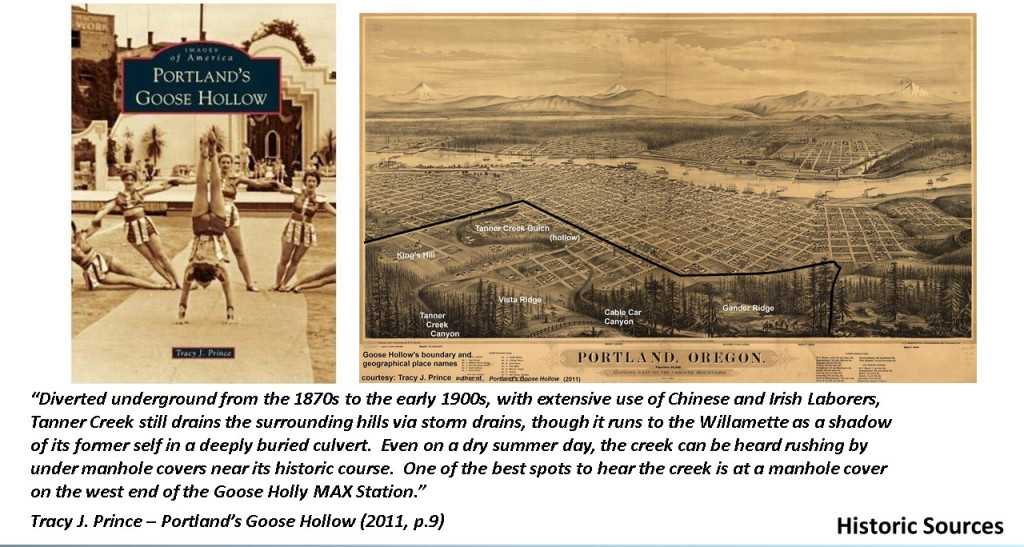

A few folks share this passion, such as David James Duncan, who talks of disappeared streams in his book ‘My Story as Told by Water’ (2002) and historical account from folks like fellow Tanner Creek nerd Tracy Prince, who has authored some great accounts of the areas in Goose Hollow and Slabtown, evoking origins of place names, connections to hidden creeks, and tying this together with the rich history of Portland’s development.

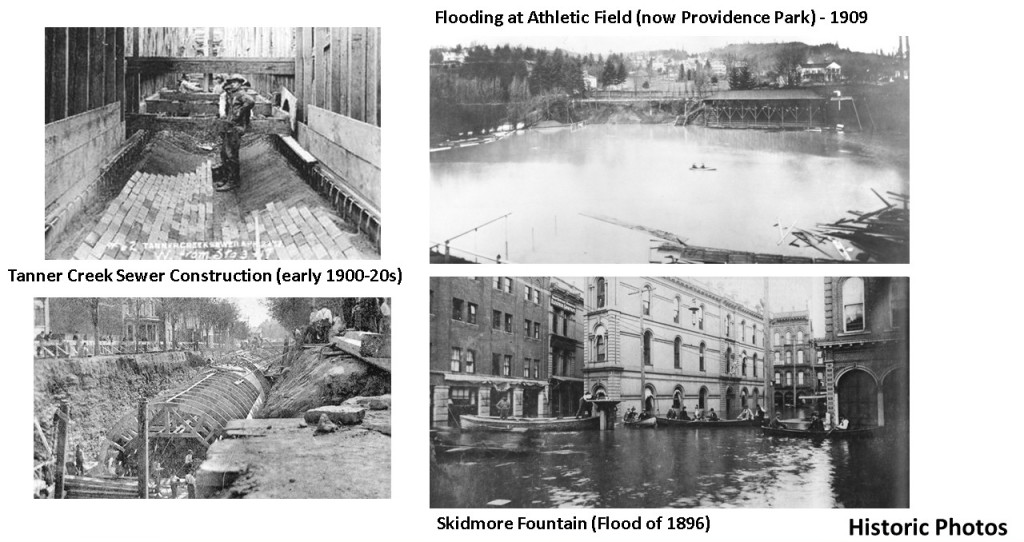

Many layers interact in painting the picture of hidden hydrology. Photos are another great resource – with historic scenes of sewer creating, as well as floods and other historical events.

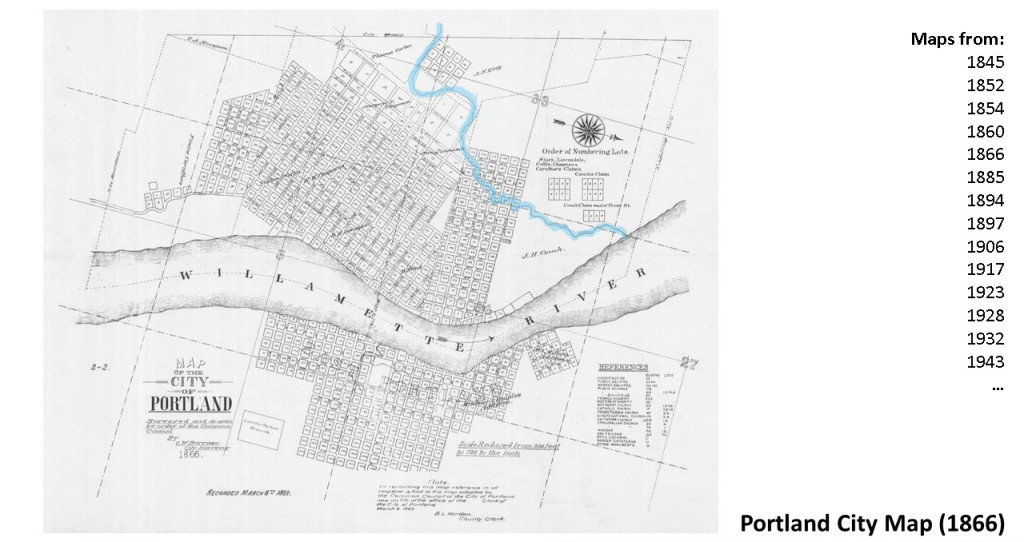

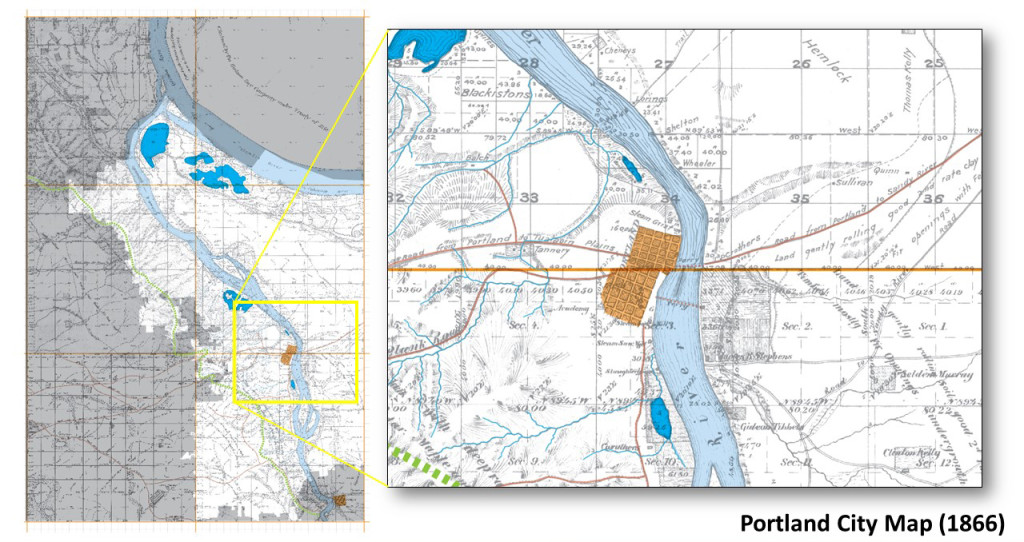

Beyond the Cadastral Survey, a wealth of maps exist, ranging from the mid 1850s through today – which paint a temporal portrait of the path of waterways over time – such as Tanner Creek, here shown still in existence in 1866.

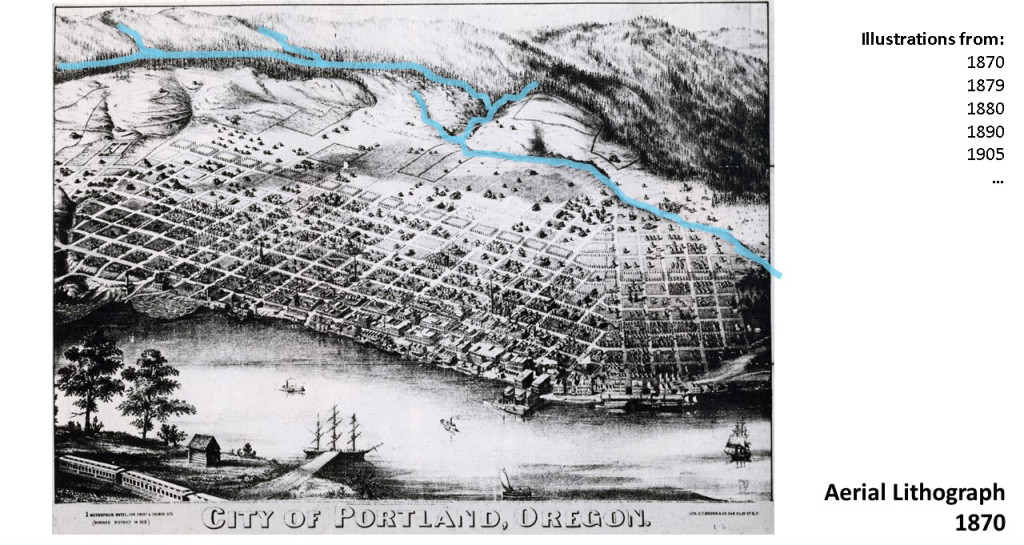

And through an illustrative Aerial Lithograph here in 1870 – again showing the Tanner Creek drainage from the West Hills through the north portion of downtown.

Map Making

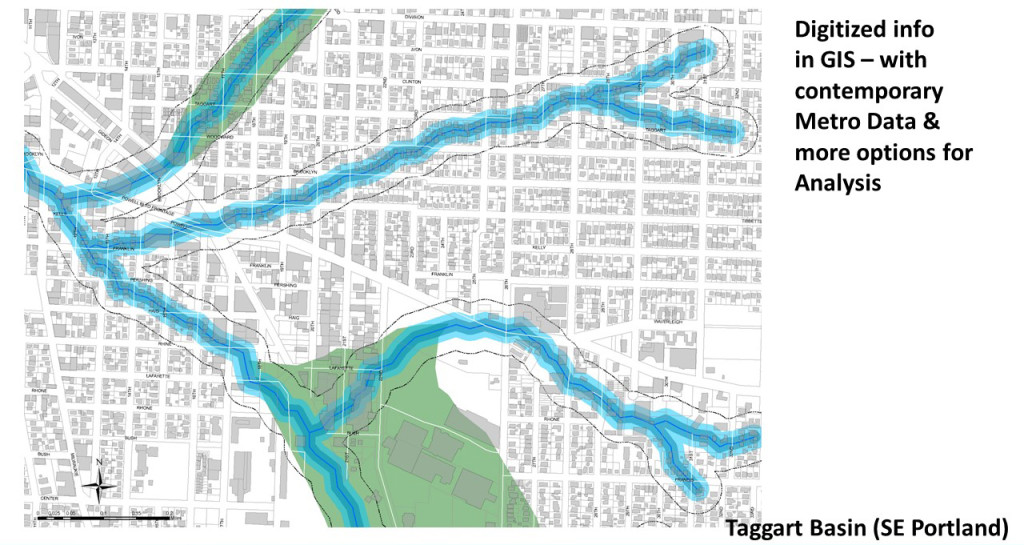

Using these tools we can start to craft maps that take the historical and overlaying information – in this case a composite of Cadastral survey mapping, amended with other information, notes, and annotations – a layered history in map format. These could easily be hosted online (a future plan) for additional input and integration with stories, photos, experience.

The process of extracting this information from the survey – shown here in a few steps – involves 1) referencing the historical layers, 2) adding streams and other water bodies, 3) adding additional info such as wetlands and other topographic featueres, and 4) georeferencing and overlaying the historic with the current day mapping. A reverse map regression that allows us to create an interesting connection between then and now.

Because the Cadastral survey is based on the Public Land Survey System (PLSS) – the township, section, range geometry (see the faint orange lines in the map above allow the historic and modern to overlap with reasonable fidelity through cartographic rectification. The maps then, overlaid with GIS data – then digitized into shapefiles with linked data – start to allow us to provide some more detailed analysis – such as for instance, correlating basement flooding in proximity to old streams?

Interventions: Tours

The second part of the talk focused on interventions – as the maps are compelling, but the ability to use them for actions are key, both in terms of expanding the validity of our interventions, but also to connect folks everyday to their hidden nature.

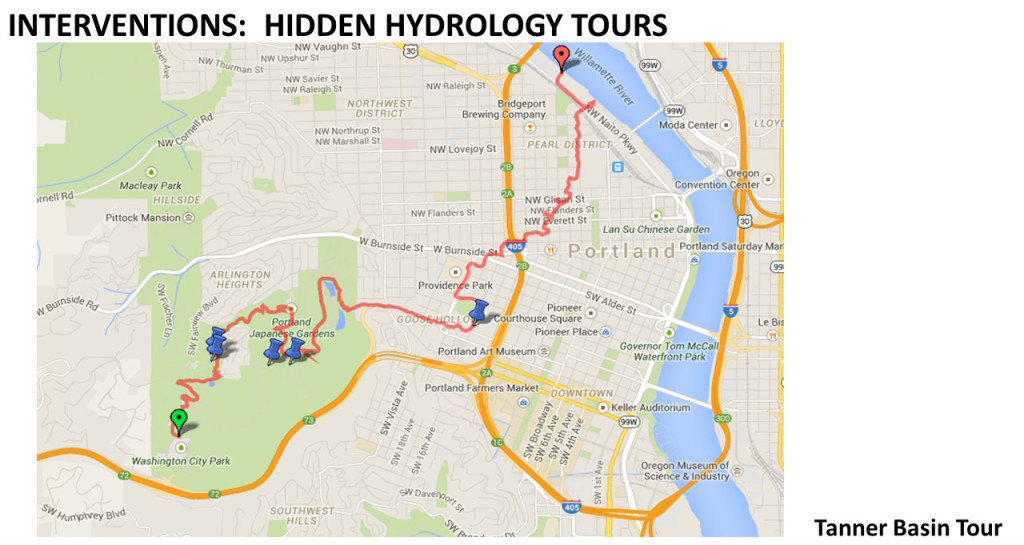

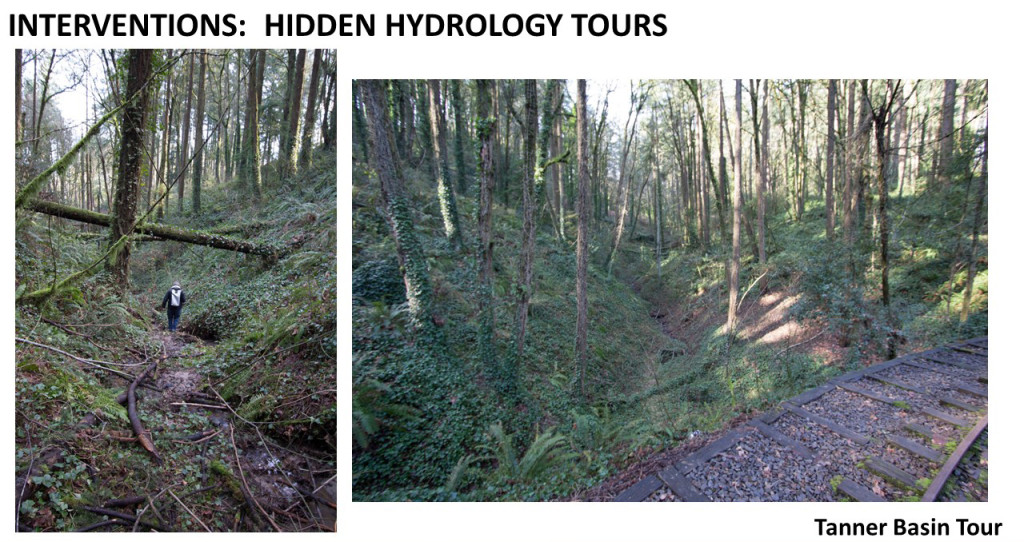

My colleague Matt Burlin and I have been talking about tours of the Hidden Hydrology for some time – so recently took the field maps for Tanner Creek and traced them from up towards the headwaters near Washington Park Zoo, down through the west hills and through downtown.

There are portions that still exist – albeit in a somewhat degraded form – but the visceral thrill of seeing this stream was compelling – The immersion in the sounds and experiences of these remnants is worth further visits.

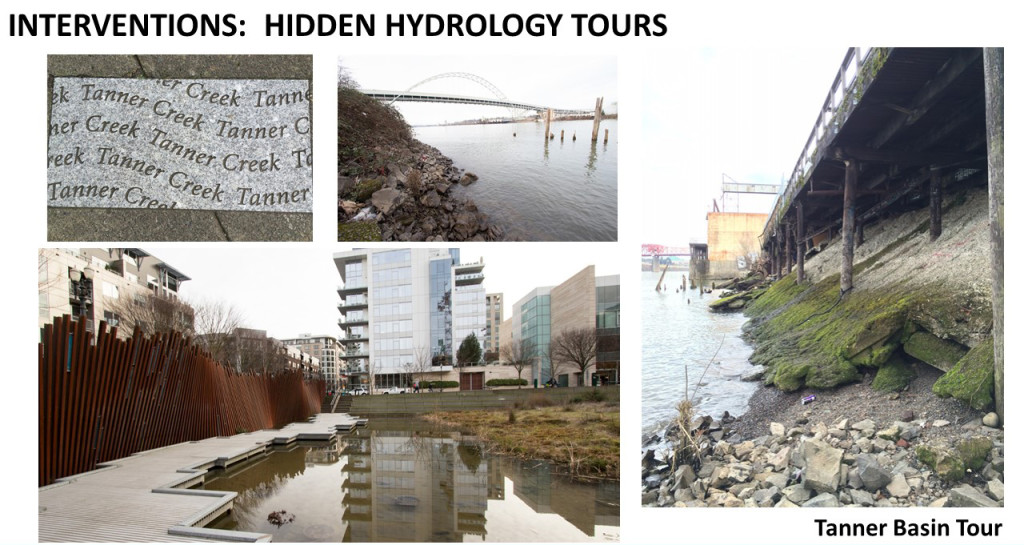

And as you get to the urban sections, the natural remnants make way to a creek completely hidden – save a subtle topographic cue and some cultural interventions of markers and Tanner Springs Park, before getting to the current outfall location in the Willamette, near Centennial Mills.

Interventions: Art

How do we interact with that which is hidden, bringing lost layers of history back to the surface. Some great art installations provide inspirations that could be applied to hidden hydrology, for instance the Freen The Billboards project (which used fixed viewfinders to overlay images on billboards)…

Could be applied in zones to allow one to click through a series of images that show the stages of current, mapping, routing, and location of historical waterways – in this case a simple illustration of how this would work for Tanner Creek.

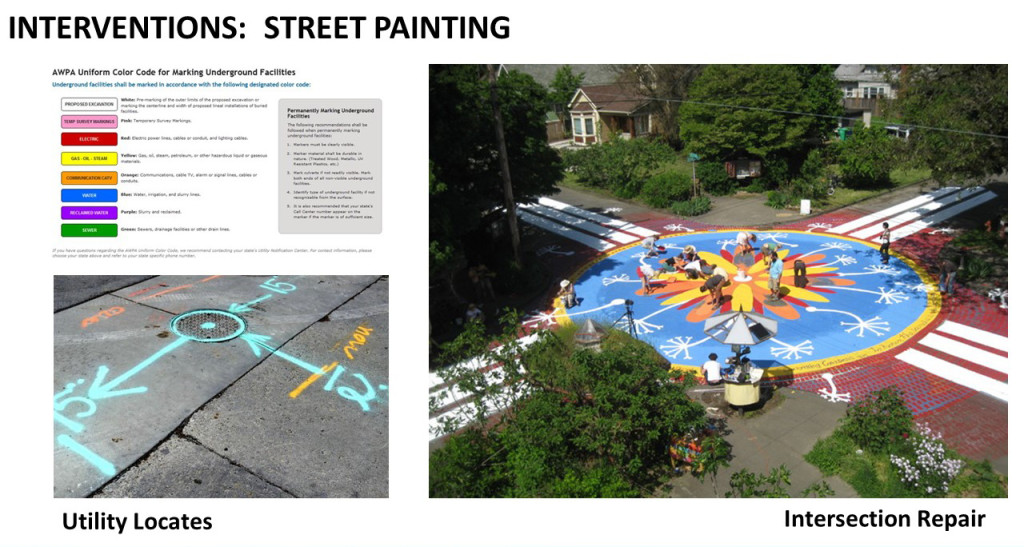

And drawing from the functional aspects of utility locates with the community artistry of intersection repair…

…one could imagine a meandering Tanner Creek weaving its way through downtown and northwest Portland streets, taking the idea of a couple of markers in the sidewalk to a much higher level of engaging and awareness in the underlying historical systems.

Thinking beyond a map or a kiosk with some informational interpretation, the array of interventions together provide multiple ways to engage, and coupled with technology could yield self-guided walking tours, vivid sound maps, and immerse multi-media experiences.

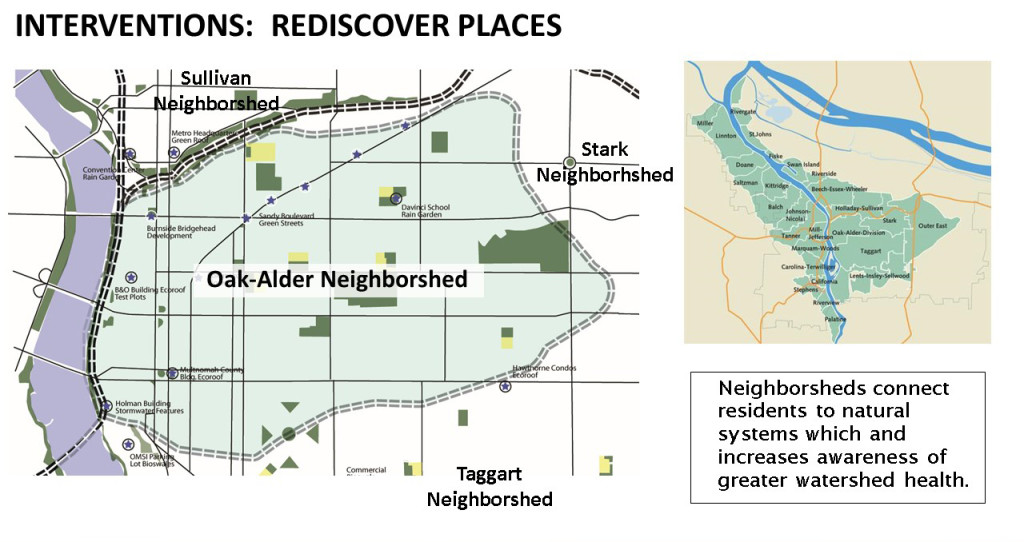

Neighborhsheds

On a larger scale, the idea of Hidden Hydrology inspires thinking about community and our connections to each other. The concept of Neighborsheds, which i coined in the mid 2000s and presented at the ASLA National Conference about – involves using these natural drainages to redefine neighborhood boundaries. By rethinking political or cultural boundaries defined outside of natural systems, we can reconnect to our place in new ways. This knowledge is perceptual on one hand – but can engage folks in shared commitment – because if you’re in the neighborshed, all of your actions become innately connected in you cumulative impact downstream.

Urban Ecology

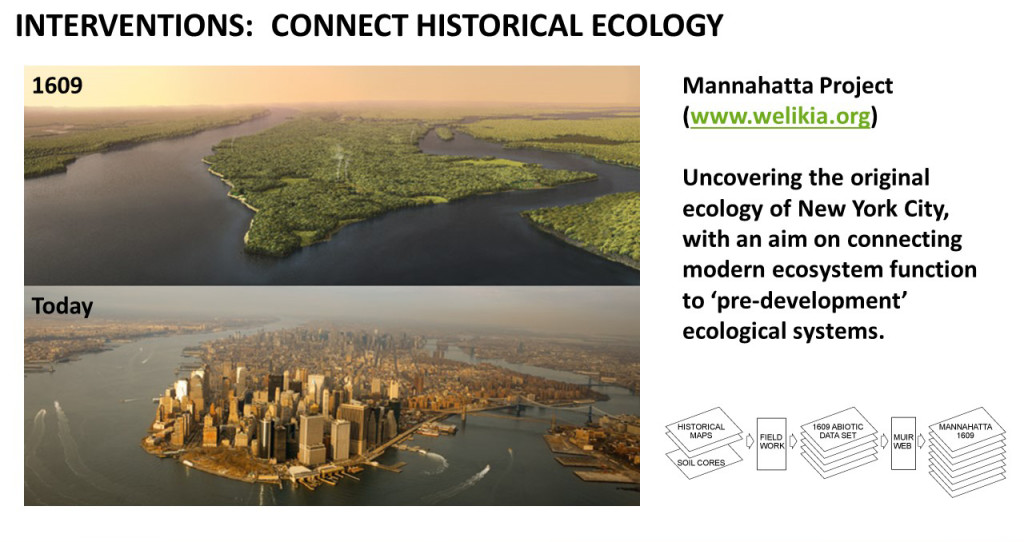

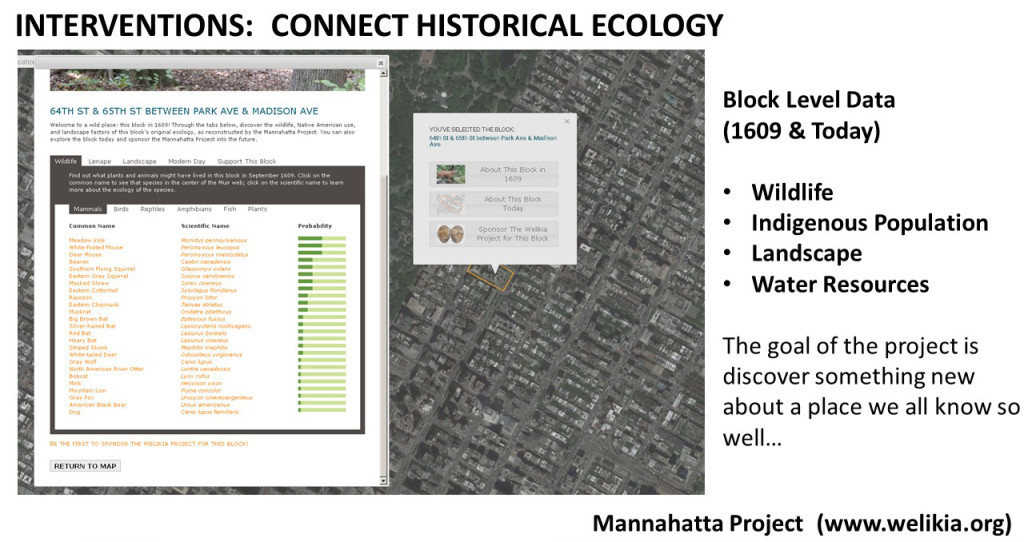

Finally, for me the concept of the Hidden Hydrology is tied to the larger ecological history. There is no better project to illustrate this that the Mannahatta Project (read more on a post here) which in it’s broader incarnation as The Welikia Project, takes the notion of historic mapping and blends field observations of biotic and abiotic factors in a rich and illustrative composite that is both rigorous and compelling.

My call to action, to create this detailed historical ecology for Portland, blending historical mapping with history, archaeology, anthropology, ecology, and other disciplines to paint a vivid picture of this historical ecology.

Beyond being fodder for art and culture, defining neighborsheds, or ways of engaging in urban exploration and wayfinding – there are some key opportunities available with this information. This can be inspiration for design interventions, can guide decisions about habitat, ecology, water, runoff, vegetation, and other factors, not in a general sense but in a block by block, historical watershed and stream basin scale.

The overlay and congruency with the hidden streams and our subsurface pipe systems is no accident – each are governed by system conditions of gravity. One is surficial and the other is hidden, so opportunities for making adjustments to the gray systems can be augmented with opportunities to use the green systems – with potentials for daylighting, integration of green stormwater infrastructure, and replication of pre-development hydrology. These decisions aren’t just based on current conditions (i.e. paved, permeable, landcover), but can be guided by understanding and modelling the pre-development hydrology – the best guide to how a particular basin wants to act by referencing how it worked before we altered it.

Finally, the concept of a pre-development metric is used for many things – to set stormwater management goals, to measure runoff in site and basin scales, and to set targets for sustainability for ecodistricts and other planning scale efforts. The return to the ‘native forest’ is a generalization of the pre-development condition, and also becomes a technological construct. Rather than pre-development condition, let’s thing of historical ecological function, which begins to not just provide us with numbers to meet, but also blends the vegetated, the ecological, the habitat, the cultural with the historic sounds, smells, textures, and colors the historical places before we forever altered them.

We won’t restore these to their natural state in all but a few selected places, but if we can restore, through metaphor, interaction, and intervention, the experience of these places, blended artfully with what they are now – places to live, shop, play – we reveal these hidden layers of inspiration to the urban experience.

A short video of the presentation is in development – and a longer follow-up, brownbag session is in the works – so look out for details.

interested in the source and pathway of westward heading streams such as Beaverton Creek and Fanno Creek. Where do they start? Where are they hidden. Any info on that would be of interest. Thanks, Art

Art.

The Cadastral Survey maps continue west from Portland (I’m just showing Portland as that’s been my focus). I’ve not digitized these zones to show their relationship to current – but you could download the GLO maps for that area and see what was originally surveyed – http://www.glorecords.blm.gov

Hi, thanks for the interesting article! I found it while looking for resources to help a friend who’s running into trouble due to the hidden hydrology of Portland.

Two years ago, my friend bought a house on SE Oak Street, between 18th and 20th. As we can see from the “Disappearing Streams” map, that section of the Buckman neighborhood is built right over one of these streams. Apparently, every house on his street has a sinking foundation. My friend loves old Portland homes, though, and figured this would be a good opportunity to restore one. He wanted to have the foundation rebuilt and finish the basement, too.

The project got under way in April of this year, and now it’s at a standstill. The creek situation beneath the house is so bad, with all of the soil looking pretty much like mud, that the project has gone over budget by more than $100,000. He’s out of money, and his house is stuck up in the air.

So many houses are built on old creek beds. Many people are potentially facing the same problem that my friend is if they attempt to restore the foundations of their homes. I’d like to help my friend get some assistance here, or at least spread awareness of this story. Do you know if the city of Portland is somehow to blame in this situation, or would it be up to the contractor or architect who took on the project and told him to go for it?

Thank you for reading! Any insights you have on the matter are greatly appreciated!

Madeline

Very interesting article! I wonder if you were able to prepare the “short video of the presentation” that you mentioned above. If so, would you kindly share? Thank you in advance. Best,

I was working on the video w voiceover, but got busy and never finished it – good reminder to wrap it up – and i’ll post when done.

Thank you. Best of luck 🙂