A great article in the Guardian on an upcoming work (Landmarks) by nature writer Robert Macfarlane on the ‘rewilding of our language of landscape’. I was not familiar with Macfarlane, but the takeaway of the connection between language and understanding of natural systems is captured in the subheading:

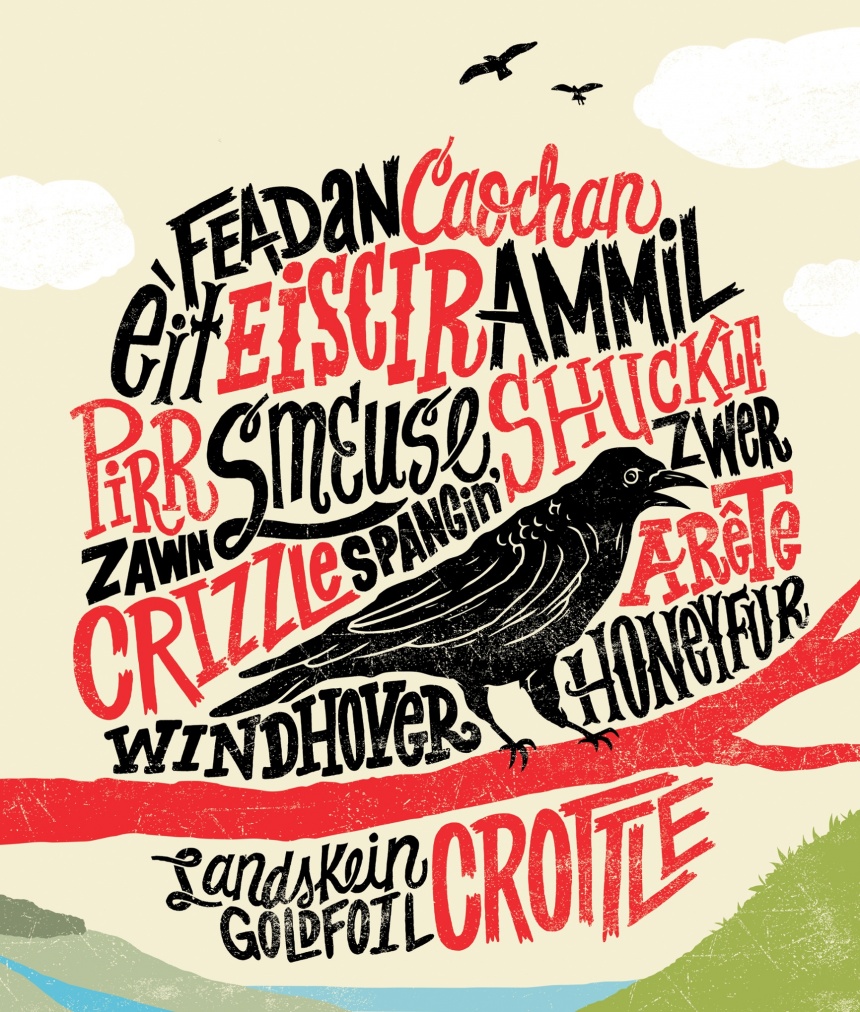

“For decades the leading nature writer has been collecting unusual words for landscapes and natural phenomena – from aquabob to zawn. It’s a lexicon we need to cherish in an age when a junior dictionary finds room for ‘broadband’ but has no place for ‘bluebell’”

Macfarlane tells the story of the Oxford Junior Dictionary, and the culling of words – ostensibly to make room for more relevant words – often was at the expense of nature. As he mentions: “A sharp-eyed reader noticed that there had been a culling of words concerning nature. Under pressure, Oxford University Press revealed a list of the entries it no longer felt to be relevant to a modern-day childhood. The deletions included acorn, adder, ash, beech, bluebell, buttercup, catkin, conker, cowslip, cygnet, dandelion, fern, hazel, heather, heron, ivy, kingfisher, lark, mistletoe, nectar, newt, otter, pasture and willow. The words taking their places in the new edition included attachment, block-graph, blog, broadband, bullet-point, celebrity, chatroom, committee, cut-and-paste, MP3 player and voice-mail. “

Through travels and noting place words for nature, Macfarlane captures what he terms a ” …Terra Britannica, as it were: a gathering of terms for the land and its weathers – terms used by crofters, fishermen, farmers, sailors, scientists, miners, climbers, soldiers, shepherds, poets, walkers and unrecorded others for whom particularised ways of describing place have been vital to everyday practice and perception.”

While the list would be interesting in a cultural sense, he captured, gleaned, found contributors, and collaborators in the collection, and the potential of such a diverse lexicon.

“It seemed, too, that it might be worth assembling some of this terrifically fine-grained vocabulary – and releasing it back into imaginative circulation, as a way to rewild our language.”

Divided into 9 sections “Flatlands, Uplands, Waterlands, Coastlands, Underlands, Northlands, Edgelands, Earthlands and Woodlands” the collection is admittedly incomplete due to the sheer variability in language and place. As he mentions “There is no single mountain language, but a range of mountain languages; no one coastal language, but a fractal of coastal languages; no lone tree language, but a forest of tree languages. ” The goal is not comprehensiveness, but to evoke feeling of wonder in the shape and sound of the words and their connections to the places they are connected to.

Tons more in the article to read – and it also hints that the book may be well documented visually, with some stunning photographs captured in the article (all images from the Guardian) by Macfarlane and others to illustrate the ideas.

The lexicon is predominately around the region encompassing Britain and Ireland where Macfarlane ranges, but it brings to mind classic texts like The Language of Landscape by Spirn, and Home Ground – a more specific lexicon of the American landscape edited by Gwartney and Lopez.

Our connection and disconnection with the concepts of landscape as a word and as a concept is long-standing. This goes for the general public, but is also acute in dialogue on the role and focus of landscape architects, where dialogues about landscape span decades and include the cultural landscape of JB Jackson and the landscape urbanism of Waldheim and Corner to boot.

Few other professions are so fully rooted in the concept of landscape, and as we debate the mandane labels for our new creations (green roof vs. ecoroof; green stormwater infrastructure v. sustainable stormwater; etc.) it’s good to find ground (literally and figuratively) in a rich heritage of language of the landscape.

Surely worth a read, and perhaps some regional repetition around the globe – a world lexicon of nature literally defined by culture.

Main header image : Làirig – ‘a pass in the mountains’ (Gaelic). Photograph: Rosamund Macfarlane (via Guardian)

(story via twitter from Geoff @BLDGBLOG)

One thought on “Language of Landscape”