One thing of note in Seattle is that it is a city of varied topography, and that this obviously guided the evolution of where settlement occurred, while creating districts and landmark areas (many ending with ‘Hill’). An interesting post related to this topographic urbanism is the seismic stability of my new city. From the Seattle Times, ‘When Seattle shakes from quakes, it’s going to slide, too’ provides a good snapshot of the impact of an earthquake on hillsides and the buildings dotting them.

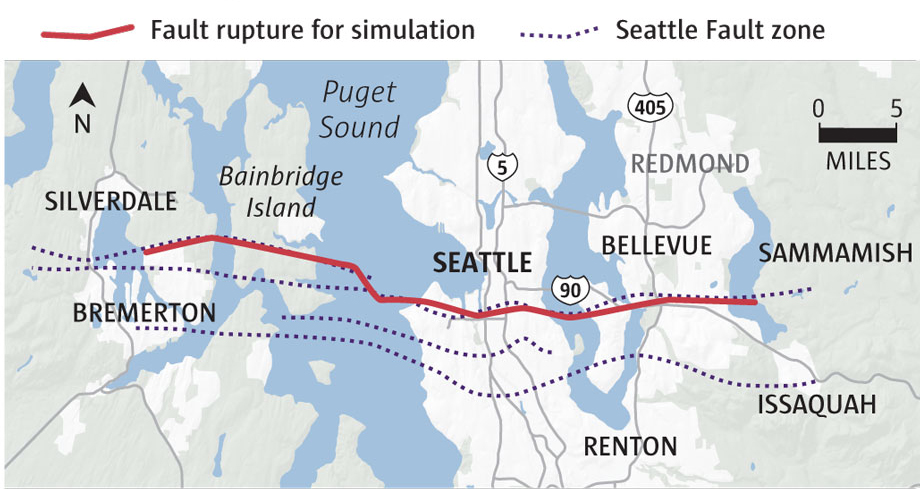

University of Washington researchers performed a study which used simulation on a ‘fault rupture’ that transects the City of Seattle to see the impact. The results are summarized in the caption from the Seattle Times:

The issue is not just the damage, but the impact of these slides, as lead researcher Kate Allstadt mentions, in addition to “…widespread damage to buildings and infrastructure caused by the quake itself, landslides would compound the city’s problems and slow its recovery.”

This is a common issue in many cities on the West Coast, and a history of seismic activity coupled with slides is prevalent throughout the region:

The Puget Sound-area landscape is pocked with scars from slides triggered by ground shaking, but the worst of them occurred long before cities existed here. The last quake on the Seattle Fault, about 1,100 years ago, shook the ground so hard that entire hillsides slumped into Lake Washington, carrying intact swaths of forest with them.

A recent earthquake in 2001, for instance, set off over 100 landslides, according to the article. This continuing threat of instability has interesting dimensions, particularly based on how much moisture is present, as dry soils yield far less damaging slides, at least in the models. Unfotunately, many of the areas that would be impacted aren’t shown on current landslide risk maps, including West Seattle, Beacon Hill and Mount Baker. A map shows the major risk areas.

While it’s obvious why this matters, in terms of health and safety, most earthquake specific action focuses around the. As mentioned in the Seattle Times article. “According to one scenario, a magnitude 6.7 quake on the Seattle Fault could kill 1,600 people and cause $33 billion in damage. That analysis glossed over the damage caused by landslides, but in major quakes, collapsing hillsides can cause as much — or more — destruction than the shaking itself, Allstadt pointed out.”

This additional cost and issues with access and cleanup mean serious study should be conducted related to how to deal with existing development in these areas, and what this means long-term for these areas of the city essentially waiting for the right event to collapse.

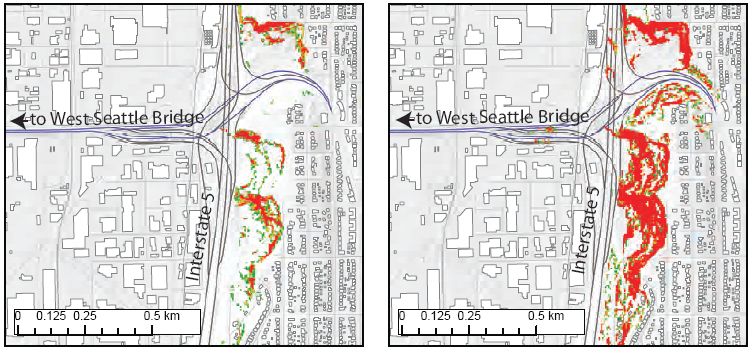

Another interesting article from The Atlantic Cities: “Seattle’s Hilly Neighborhoods Could Slide Into the Water During the Next Earthquake” delves into similar terrain looking at the UW study in more detail in areas of . Writer John Metcalf looks at the smaller micro-impacts that the study (for instance see below), and the distinctions of the dry vs. wet scenarios. The context is important, as in the case below, the impacts to major transportation routes in large landslide events could hinder response to areas of the City, in addition to the immediate damage.

The summary is, that we need to be aware and prepared – as a region, but also in specific areas we know are going to be impacted and those that are key elements of the response infrastructure system. We don’t know when, but it could be sooner than we think. As mentioned in the Atlantic Cities article:

That’s why it’s crucial to start prepping, says Allstadt – finding out what microregions are especially vulnerable, planning rapid responses in and out of these zones, predicting what sewerage and electric infrastructure could be knocked out, educating home-buyers on the risks of living on uncertain slopes. “It could be now or a couple thousand years,” she says. “We just don’t know.”