A couple of interesting articles in the NY Times from Sunday, November 24th, posit scenarios for the implications of climate change and cities. James Atlas in an OpEd piece ‘Is This the End?‘ discusses recent events in Venice, New Orleans, and Indonesia and the more recent flooding due to Hurricane Sandy, in relation to our linear view of history. He references a study by the New York City Panel on Climate Change on the impacts of rising sea levels, warming temps, and impacts (hopefully not to the degree seen below) on cities and infrastructure.

The takeaway is that history is not linear, but an aggregation of the random and interspersed events – which we interpret into things at an end of a line of events – but rather the end is just our current moment. As noted by Atlas:

History is a series of random events organized in a seemingly sensible order. We experience it as chronology, with ourselves as the end point — not the end point, but as the culmination of events that leads to the very moment in which we happen to live. “Historical events might be unique, and given pattern by an end,” the critic Frank Kermode proposed in “The Sense of an Ending,” his classic work on literary narrative, “yet there are perpetuities which defy both the uniqueness and the end.” What he’s saying (I think) is that there is no pattern. Flux is all.

Related, Benjamin Strauss and Robert Kopp, discuss the impacts in ‘Rising Seas, Vanishing Coastlines‘ and the fact that, due to a study by Michael Schaeffer et.al. in Nature Climate Change, even with our best efforts, sea rise change will happen – and 6 million people in the United States living in land less than 5′ above high tide. There will be more flooding, and storm surges will be more severe. We can slow this but not totally stop the rising tides. A link to the Surging Seas website offers “Map pages show threats from sea level rise and storm surge to all 3000+ coastal towns, cities, counties and states in the Lower 48.” Data is available as well – so make your own maps as well!

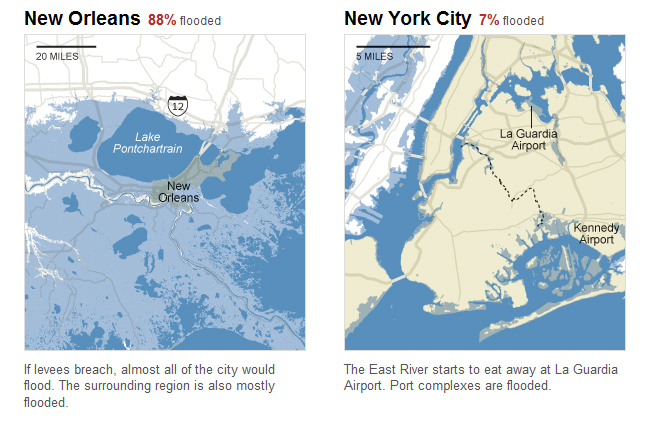

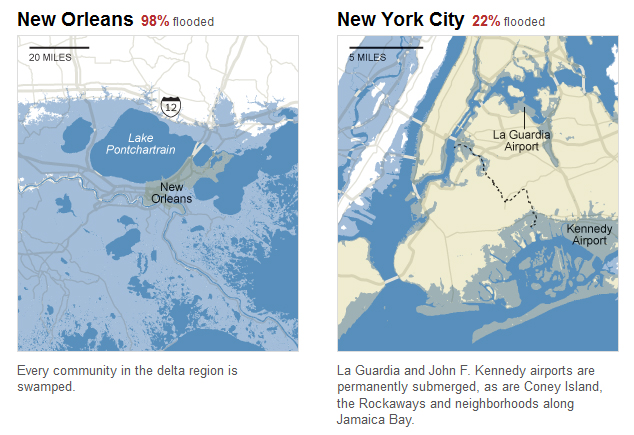

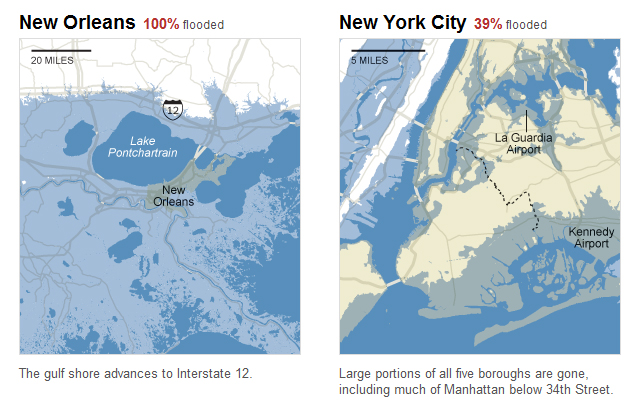

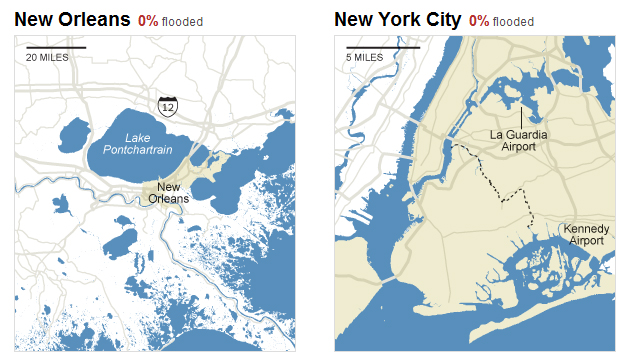

A series of maps accompanying the article is ‘What Could Disappear‘ shows some maps using this data – and it’s worth spending some time checking out. A quick snapshot comparison of New Orleans and New York shows changes due to 0, 5ft (probably rise in 100 to 300 years), 12ft (levels in 2300 with moderate environmental change), and 25ft rise, which is a potential historical level (obviously based on many caveats, but an interesting conceptual exercise nonetheless.

Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy were some indication of the relative catastrophe that happened – and a hint at the amount of devastation possible due to flooding and storm surge. The difference is a 5′ rise causes massive devastation in New Orleans (88% flooded) whereas it is huge but much less impacting in NY (7% flooded). As we’ve seen, loss of life and the billions of dollars needed to fix these two most recent events is significant. A hint perhaps, but a small one in the grand scheme.

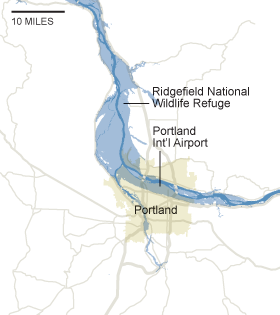

Portland, Oregon isn’t a bad spot to be, due to our inland locations, as the worst case maps (25 rise) leaves much intact, with the exception of an underwater airport.

As Strauss and Kopp conclude, we can’t just reduce impact or prevent them through technological or other solutions – but need both approaches.

There are two basic ways to protect ourselves from sea level rise: reduce it by cutting pollution, or prepare for it by defense and retreat. To do the job, we must do both. We have lost our chance for complete prevention; and preparation alone, without slowing emissions, would — sooner or later — turn our coastal cities into so many Atlantises.

There’s definitely much to think about from a planning level. The impacts, even with conservative assessments, are massive – especially when it’s not isolated to a weather event but based on global sea rise. The implications for infrastructure and our need to adapt cities (sewer, electrical, roads, and more) – both new planning and retrofits – for climate change is not just a luxury, but rather is a vital imperative for survival.