One of our supplementary readings for the Shrinking Cities group is the recent essay by Jerry Herron on The Design Observer entitled ‘The Forgetting Machine: Notes Toward a History of Detroit.‘ The author is from Wayne State and has been a resident of Detroit since the early eighties, so it avoids some of the outsider rhetoric, but he still differentiates himself as coming from out, not within. Read his essay, as this is more of a ‘notes on notes’ take that is my reaction and parsing of his essay. Worth a look.

:: image via Design Observer

The idea of Detroit as a industrial powerhouse declining into a bastion of cliched ruin-porn makes it a much talked about as a cultural touchstone of the shrunken city phenomenon of the US. Referred to by artist Camilo Jose Vergara and ‘American Acropolis’, the idea of preserving the ‘ruins’ as a tourist attraction, much like the Greeks, leads Herron discusses a similar relationship to the Roman ruins, After commenting on the disinterest by locals and the seeming paradox of outsiders being more fascinated by the city than those who occupy it, he turns this around as asks a powerful question:

“who understands better what the place really means: the person who tries to remember it, or the one who lets it go?”

This becomes a fundamental dilemma surrounding a place that will never return to it’s original state – but is not dead by any means. I think of the lively energy of the contemporary city that I visited in the Fall, surrounding the 1000+ year old ruins of Rome and see a parallel in the larger lesson – that things always change, but the way we engage in that change, and in the sense of Detroit, the deterioration, tells much about us as a society. As mentioned, the concept of what happens in Detroit isn’t special per se, but for the fact that it is happening within a crumbling environment. Thus as art, mentions Herron: “things once tragic become beautiful — images for artistic appreciation — with the ravages of daily life being redeemed by photographic dignity.”

I share the same fascination with the City of Detroit in images and through my visit and rumination since 2007 – and it puts me in the camp of the gawkers and outsiders, at least to the point where I peruse and am fascinated, but don’t buy, the coffee table ‘ruin porn’ books like Detroit Dissassembled, and the newer The Ruins of Detroit (with an introduction by Thomas Segrue). What is quoted by Herron from John Berger as ‘mystification’, where we distance ourselves from the actual phenomena at work – good and bad – and giving them a remoteness by making things art.

:: image via The Ruins of Detroit

The statements made by the photographs, particular referencing those in The Ruins, do not capture the essential rise and fall of Detroit, but seem to bask in the ‘dead zone’ shivering aesthetic of destruction, which leads Herron to posit: “Perhaps the cliché-propagating idiom of ruin porn is so powerful that it simply takes over, duping otherwise intelligent artists into a tedious banality that not even the volume’s pretentious scale and price can conceal.”

So i know I shouldn’t like the ruin-porn, but standing in the midst of it, in Detroit, is to experience first-hand the reality. Perhaps it is somewhat less sanitized and ‘framed’ as in the photography, but the fact of it’s very reality and other-worldly sense that this couldn’t be happening, is part of what I think the art is trying to capture. For me, it was summed up in the spectacle of the Michigan Central Station, which was one of the first massive ruins we encountered, and I still have a vivid memory of the experience (and no photos – i was literally absorbing and didn’t think about taking a photo, which is rare).

:: image via Time

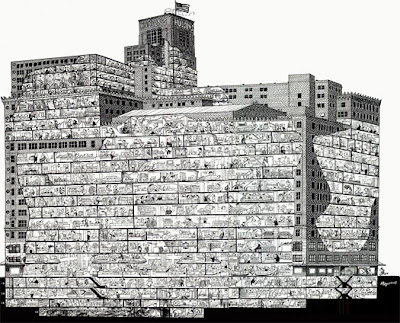

It’s reductive, and it limits the stories behind the former beauty, and the nasty racial discrimination that was at work in the creation of something like the large Hudson’s store on Woodward Avenue, captured in this image that shows the cutaway of the various departments inside the hive of mid-century activity which was vital to the “making of shoppers, like the making of citizens, was an essential function of both store and city, especially the city of middle-class arrivals made possible by the flourishing of modern industry”. This idealistic experience is another cultural ruin that no longer exists (as it was demolished by changes in commerce) – much like the building in which it used to happen.

:: image via Design Observer

The same fates, to a differing degree, befell many sites, like Hudsons, but the overlay of the old (ruin) and the new become something similar to Rome – a cafe right outside the Pantheon, or a gelato stand at the Colosseum… In Detroit, the Michigan Theater, for instance, was an architectural gem from the 1920s, which in the words of Herron was somewhat rudely transformed into a parking garage… “The old Michigan Theater is one of the most suggestive sights in the whole city of Detroit: neither an abandoned ruin nor a precious, restored fetish, but a working statement about making do with the past. The tenants of the offices adjacent to the theater threatened to move out unless they were provided with secure parking, so that’s what the landlord improvised out of the otherwise useless auditorium. And that is the genius of the place.”

:: image via Design Observer

As mentioned, the mechanism is based on the ‘mystification’, but is really what Herron calls ‘site-specific forgetting’ in which those people who occupy the city are intertwined within the processes of destruction – and it is not a binary question of one or the other side of a coin.

“The ruin of urban space becomes a participatory drama: memory versus forgetting, the city dead or the city alive. The trick is seeing both at once, and comprehending them as equally true and mutually implicated.”