We complete this aqueous journey (don’t you love when something simple turns into something wonderful?) and we end with some brutal reality and some hope as to our ability to turn the tide of our technological wrong-doing. I would posit that perhaps the most compelling reading of the year so far in landscape architecture were the two posts from Pruned in late-February 2008: ‘Treating Cancer with Landscape Architecture‘ (Feb. 19) and ‘Treating Acid Mine Drainage in Vintondale‘ (Feb 22). Together, in at least in the expansive realm of landscape architecture, the combined tale of these projects and the ability for landscape architecture, ecology, and design to actively provide not just sustainable design, but restorative design – definitely was a moment of reinvigoration into the profession.

:: Walk on Water – image via Atelier A+D

To avoid confusion, I will give an overview of each project and sum up at the end some thoughts. I’ll keep the overviews brief, as Pruned as always does a wonderful job of giving quite comprehensive information on both. First, the proposed Phytoremediation of Silver Lake proposed by Cal-Poly Pomona Landscape Architecture Department offers a comprehensive view of the potential of landscape plantings to restore and reclaim a blighted landscape. In this case Silver Lake and nearby Elysian lake, reservoirs that supply drinking water to greater Los Angeles, which both have high levels of bromate, a known carcinogen.

:: Silver Lake – image via Pruned

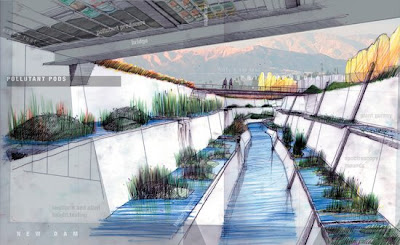

In a nutshell, the proposal goes as such (a more complete overview can be had via Pruned) Terraces or ‘modular biopods’ provide remediation for the pollutants found in the waterways. Once cleansed, this water is stored in a subsurface tank prior to use. The water levels are raised to create more aesthetic park-like activities – which are infused with opportunities throughout to provide education on water pollution, use, and phytoremediation.

:: images via Pruned

As Pruned sums up: “It’s landscape turned into a therapeutic and preventive medicine, applying natural processes into an artificial apparatus.” In this regard, the functional/artificial processes are linked closely to nature’s ability to provide cleansing via plants. Thus, there is a link to perhaps one of the best links for phytoremediation by John W. Cross – which is pretty accessible. I remember stumbling upon this site a few years ago when researching toxic removal with vegetation and it’s pretty comprehensive. Pruned also mentions some good bibliography of phytoremediation as well.

The second project, the AMD & Art Park is a great project with a story of. I read about this recently as well in a great article in Orion that showcased the work of T. Allan Comp. AMD stands for Acid Mine Drainage, which is of course just what one thinks of when considering art and open space. The proposal is amazing in simplicity, ecology, and design. Comp brought together a multi-disciplinary team including Robert Deason, a hydrogeologist; Stacy Levy, a sculptor; and landscape architect Julie Bargmann, of L+U favorite D.I.R.T. Studio.

:: image via Pruned

An overview, via the Green Museum: “Polluted water flows along the colorful plantings of a “Litmus Garden” into a series of large gravity-fed water treatment ponds lined with crushed limestone to neutralize the pH and remove toxic metals. The water continues through bioremediation ponds and into an educational History Wetlands area which further purifies the water before it joins a nearby river.”

The ‘litmus garden’ is not just a name, but an evocative feature playing on pH using a range of native plant species to display these (via Pruned) “Small groves or bands of thirteen native tree species were chosen for their autumn foliage colors. In the fall, the Litmus Garden trees will turn deep red around Pond 1 and grade through orange and yellow to blue-green at the end of the treatment system in Pond 6, creating a visual reflection of enhanced water quality — and a great reason for a Vintondale community fall celebration.”

:: image via Pruned

Via Pruned: “The treatment zone is easily distinguished by a series of 7 keystone-shaped treatment ponds. No cutting edge nanotechnology or the latest transgenic organism or even heavy machinery is used. Turning the highly toxic water into one that you can swim in is done with elementary physics, chemistry and biology. Regular limestone, for instance, is applied instead to lower the water’s acidity. Plants simply dying off and decaying in the winter and then returning in the spring also helps to change its pH level. Even gravity is utilized to help suspended metals settle out of the AMD.”

:: image via Pruned

The park has been evolving for over 15 years, and has become a vital park to the community of Vintondale – offering ballfields and usable open space. The lesson is not the technology or design, but the end-goal, as Eric Reese in Orion stated: “…one of the most important elements of Vintondale may not be its water-treatment system or its sculptural installations, but rather its function as a potential model for many other such projects across the country.”

And they brings us to the end of this journey along the many flowing courses that water takes us in design, planning, and daily life. Concluding this 3-part series on Aqueous Solutions, I’m struck by the wide range of scales and strategies necessary to both mitigate and solve some of these problems with water – either supply, usage, or toxicity. It dawns on me that all of these are linked in many ways – the smallest intervention or use (read: misuse) can have cumulative impacts that leave us with shortages or pollution – or both. On a larger scale, our grand technological ‘fixes’ seldom come without collateral impacts of some sort – to social systems or micro-scales that cannot be accomodated in macro-scale planning.

Water is often pressured to do so much for humanity that it is quite surprising that we haven’t messed it up to an even greater degree. We drink it, consume it for industry, revel in it, celebrate it, recreate in it, store it, pump it, worship it, capture it, distribute it, budget it, circulate it, use and abuse it – all while bemoaning it’s loss and contamination. Much like a number of sustainable strategies this isn’t just a question of use – it’s a question of cumulative actions resulting in a large-scale impact to a vital ecological system.

Our hydrology (and hydrological cycle) cannot be circumvented for our uses without consequences. Our ecology cannot be abstracted and packaged without some viscious backlash typical of nature misunderstood. Our chemistry can destroy water supplies with minimal inputs – and all of our ingenuity can’t recapture what is lost. But there is definitely hope. By reducing our impacts, increasing our efficiency, and understanding the nature of how ecological systems function, and are innately resilient – we find the ability to repair, restore, and truly provide regenerative design strategies.

These projects should not be the special exceptions to make us feel good about the profession and our role in it. This must be the rule, the consistent truth of landscape architecture. If we continue to disregard our role in creating a better world (both as detrimental actors and as potential problem solvers) we will continue to marginalize ourselves and our true potential. Apply this theory beyond water to any issue… the real idea isn’t the material – but the message: solutions.

Backtrack: