Ok, this is two posts from CNN in the span of a couple of weeks. And I don’t actual watch CNN, except for when trapped in an airport with the constant 10 minute new cycle. But this one is pretty impressive for major media outlet… Principal Voices is a ongoing series of discussion and dialogue bringing together top minds in a range of fields… this year fittingly including a part of the series entitled: ‘Design for Good’:

In short, it’s a celebration of the role of building on changing the face of the world. “Whether it’s designing efficient skyscrapers, creating whole cities which aim to be carbon neutral or re-building out of the rubble created by natural disasters, architects are changing the way we experience the built environment, finding solutions to the ecological challenges — big and small — of the 21st century.”

:: Dongtan Eco City – image via Greenline

The title story spans some history, which gives a nice primer on ‘green architecture’ through phases of history. “Although the term “green architecture” was only coined about 20 years ago, architects have been embracing environmental or sustainable design for decades. …Today, architects are transforming our urban landscapes in ways which were previous unimaginable. Aided by cutting edge design and construction techniques, the bold new structures of today owe much to the techniques used by pre and early industrial pioneers.”

Some interesting precedents of ecological design were mentioned in the article.

The Crystal Palace (1851) is one of: “…the earliest examples of more complex climate control were designed by Joseph Paxton — who used ventilators in the cavernous vaulted roofs…” The microclimatic shift with a glass interior allowed for significant plantings of the interior atria as well, blurring the interior-exterior shift of architectural form.

:: image via BBC

:: image via Brittanica

The article goes on to cite numerous examples including Giuseppe Mengoni’s Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan (1877) and the iconic Flatiron Building in NYC (1902). There was definitely a lag in the environmental movement in the early 20th century, driven by taller building forms and technological advances in air conditioning and heating which disconnected buildings from their microclimate, and thus generated forms that no longer were required to work with the local environment.

This trend dissolved in the 1960s, with a backlash against modernism and the birth of the modern environmental movement shifting the focus back to ecology and environmental issues. While missing in the article from this historical cast is (surprise) Ian McHarg, and his influential mid-sixties planning, this ethic did shape the early and future work of eco-pioneers such as William Mcdonough and Sim van der Ryn as well as birthing such projects as Arcosanti by Paolo Soleri (1970)…

:: Arcosanti – image via Wikipedia

…and notable mid-1970s version of Veg.itecture in the form of Norman Foster’s Willis Faber & Dumas Headquarters in Ipswich, UK (1975), which is known for an expansive and usable ‘grass’ roof. (link to BBC for an interactive 360 panorama as well)

:: image via Archinform

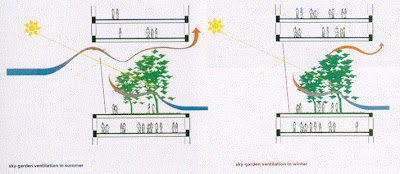

We evolve into the 90s with a lot of momentum, and this bred scores of ‘ecological’ buildings, as well as the market and industry to support them such as LEED and the UK analog BREEAM. From this came a lot of scorecard-motivated ‘eco-architecture’ that lacked anything resembling a sustainable ethic, but also some pioneering projects and ideas, such as the Bioclimatic Architecture work of Ken Yeang. His Menara Mesiniaga in Kuala Lumpur (1992) is the seminal work and much has followed.

:: image via Business Week

And the article mentions Foster’s Commerzbank Headquarters in Frankfurt (1997) dubbed the world’s first “ecological tower”. I love this building, but fail to see how it get’s the distinction of first, when Yeang’s building pre-dated it by a half-decade? From Foster’s site, they describe it as the world’s first ‘ecological office tower’… so maybe that’s the distinction? Whatever, they both are amazing precedents.

:: images via Nature in Buildings (MIT)

As the article ends, the concept is here to stay and thriving, based on these historical precedents: “Taking nature’s most enduring designs and using them to reshape our own environment is now a thriving branch of environmental architecture. Modern eco-buildings now combine to form communities, like BedZED in the UK. And eco-communities are set to form new eco-cities, like Dongtan in China.”

More Design for Good

Back to the general Design for Good thrust and digging a bit deeper, we find the ‘thinkers’ in which we get our revelatory information. Ok, so it’s a little suspect that they include Daniel Libeskind as a ‘Big Thinker’ (?), but the do redeem themselves with overviews of both Cameron Sinclair (‘Frontline Pioneer’) of Architecture for Humanity and Open Architecture Network thought experiments as well as Peter Head (‘Future Player’), who has some major eco-cred as director of urban design and development at Arup and is a major player in the afforementioned Dongtan Eco-City project.

And I probably would have skipped the entire DFG link if not for an interesting article that caught my attention on the site. ‘Borrowing from nature’ investigates the role of Biomimicry or Biomimetics in design and ties it briefly into architecture and building. From the article: “In the 21st century, architects and designers are increasingly turning their attentions to Mother Nature as a source of inspiration for their creations. …The art of copying nature’s biological principles of design is now known as biomimetics.”

:: Abalone as potential ceramics – image via CNN

We’ve covered it here prior in brief, and the article focuses on a number of product related design analogs in the Biomimicry literature. There are also some great ideas that are relevant to architecture, landscape urbanism, ecological planning and urban agriculture, worthy of exploration. These will show up periodically in future posts as they have much relevance to the discussion and I guess thanks to CNN for informative and thought provoking journalism. Kudos for bringing good design and ‘Design for Good’ to the mainstream.

Coda

As an endnote… one notable missing element of the equation is the role of the other non-architecture team members – with this reliance on the power and singularity of the architect’s role as master of all. A good thought-piece on this in Slate by Witold Rybczynski entitled ‘Architecture is a Team Sport’ discusses this thought in relation to the Pritzker Prize and it’s award to a single person.

“The Pritzker Prize promotes the fiction that buildings spring from the imagination of an individual architect—the master builder. This wasn’t true in the Middle Ages, when there were real master builders, and it isn’t true today. The modern architect works with scores of specialists, first and foremost structural engineers, without whom most architects today would be lost. Armies of consultants are responsible for everything from acoustics and lighting to energy conservation and security.” Hey wait a second, you forgot… oh whatever.

I guess the acknowledgement of ‘team’ aspect of project is slowly creeping into architectural consciousness. I actually disagree with Rybczynski when he mentions the singularity of say, the Nobel prize – as any endeavor involves more than a single person to ensure success. If the concept is to celebrate ‘ideas’ that is one thing – but specifically projects involve a team much greater than the architect, and even the design-team… it does take a cast of thousands…